Daria Khrisanfova, artist, and teacher of KhNUMY University named after Beketova

Natalya Kurdyukova, journalist, head of Kharkiv Media Hub

On the first day of Russia's full-scale invasion, an enemy missile struck her apartment in the quiet center of Kharkiv. Just seconds before that, Daria Khrisanfova, a Kharkiv artist, a teacher at the Academy of Design, the University of Urban Management, and the curator of the iconic art space "KhudPromLoft," had stepped into another room and survived. From that day on, almost all her art and atmospheric photos on her Facebook page have been accompanied by the caption "Kharkiv. We are at home."

We all experience the war differently. Daria sends out an energy of peace and love to the universe. She doesn't like to talk about a significant part of her life associated with helping the Ukrainian army, but her friends know that she directs most of the money she receives from selling her paintings abroad to support these efforts. For a unique project in contemporary Ukraine, the comprehensive publication of literary and musical materials for the modern Ukrainian opera "Blue Bird. Return," Daria Khrisanfova created a series of artistic illustrations. Thanks to these illustrations, the libretto, score, piano, and the voices of individual orchestral instruments acquired a distinctive character, delicate yet strong and inspired.

How are you now? That's the first question. Yes, how are you doing?

— Well, the question 'how are you' for us now probably substitutes for those very tender, warm sentiments that you don't express explicitly as frequently, but rather convey more succinctly. And you put much more into them than it seems. In fact, if I can put it this way, since we are in a constant state of war, I am doing well. Why well? Because I've learned to live like this. I guess I've learned, more than anything else, to name things, to give a name to not only an emotional state. I don't really like the word 'reflection,' actually."

You don’t?

— I really don't like it. Why, you might ask? Because when you're in such a state, you need not only to reflect but to think. You need to shift from one state to a completely different one. That's why I prefer the terms sensitivity and emotions. I've reached a point where I can articulate and construct narratives about these feelings, both personal and beyond my own experiences. My recent projects reflect that aspect. However, for me, my personal experience was crucial. Everyone has their unique experiences, and I agree with Kozlovsky, who, regrettably, is no longer with us. This experience of "love is our indebtedness" is something I deeply appreciate. It resonates with the idea that we are all connected through love, and we carry it with us throughout our lives.

So, you were drawing a lot back then. We met once, and your entire table was filled with your drawings. We witnessed your gradual recovery. Initially, these drawings were not very detailed. Let's say, not very precise, perhaps. At that time, it seemed to me that this continuous drawing helped you recover a bit.

— Yes, yes. Basically, I started drawing around that time. A missile hit my place on the 25th, and I started drawing a few days later. I began on the 28th of February, and even those first drawings, when I looked at them, my hand... my hand was not very steady. This drawing is perhaps like a cardiogram that's typical for me. Initially, it was quite irregular. Not in the sense of being disharmonious, but rather, it lacked reflection, failing to capture a clear rhythm. And then it started to display some sensory nuances. As I was recovering, a more transparent and sensitive line emerged, less rigid, I would say. Before that, I had experience helping in the hospital by drawing with the soldiers.

Is this before the war, you mean, or already now?

— In 2017-2018, before the full-scale war, I was there, drawing and assisting in the fields of neurology and psychiatry, working with both young men and women. This experience allowed me to understand how individuals perceive things in various neurological and mental states. However, for me, the act of drawing and assigning names to everything turned into a personal experience. So, it's essentially therapeutic. Yes, it's my own way of coping, not so much an escape but more like breathing.

I've been involved in competitive swimming for quite some time, and the ability to breathe underwater is somewhat similar to how you breathe in times of war. Learning to breathe steadily, mastering this kind of breathing, is of utmost importance, not just for survival.

Breathing in war is very interesting. Are you referring to the way we "breathe," as they say?

— Yes, because we often discuss... particularly the experience when there are explosions. For example, this morning, yesterday, today, ... I was next to the river, and I could hear very well. But when you can breathe, you're not just inhaling; you can also exhale calmly because it's very slow, and learning to do this is crucial. I draw — today, I woke up and just started drawing at that time. Even in the spring when we got hit by missile strikes, provided circumstances allowed, I drew. You can draw from 500 meters or a kilometer away, but no closer. For me, it's not so much an experience; it's likely already the state of life.

When missile hit your apartment, everything seems to have been affected, including all your pencils, which are essential for your drawing. Who helped you to still have these drawing tools?

— I stayed with Natalka Marynchak during that period, for a little over half a year. Natalka initially found small paper scraps that were left over from the hardbacks made by Yulia Maxymeyko. I began drawing on those. However, I draw a lot, so I used them up in just a couple of days. That's when Father Victor Marinchak, a chaplain, and Father Hennadiy stepped in and brought me small pieces of paper from the church. And I began drawing on those scraps. Eventually, they brought the first pencils and pens.

It was then that I realized that our classical education often emphasizes pure art, highlighting the impossibility of combining and drawing incompatible elements. Contrary to our traditional education, my experience demonstrates that you can do it, and sometimes it's necessary. During that period, doing "wrong" things actually saved me. As a teacher, I found it quite fascinating to challenge the notion of doing things "wrong" because, in the end, it led to some remarkable results. Combining oil pastels with a ballpoint pen, a pencil, or colored pencils isn't typically considered compatible since they involve different techniques. But they resulted in outcomes that exceeded my expectations. It was like rediscovering the world with childlike joy. I think that during war, many people, no matter what situation they're in, get to understand others and themselves better.

But these changes continue. Let's talk about these transformations: how people around you are evolving and how we are changing during the war.

— We're going through significant changes. There are both challenging and positive experiences in this process. Some old forms of communication become impossible for various reasons. Not because others don't understand you, but perhaps you're not willing to invest so much time in certain types of communication. Simultaneously, new forms of communication emerge, and you start connecting with people you wouldn't have considered communicating with before. You become more open and sensitive to certain feelings and wavelengths that resonate with you. This resonance works in various experiences, even in the way you breathe and interact with the world. And you develop the ability to understand people even before they speak. I agree with Tsilyk [Iryna - ed.] in some ways — it's essential to take a moment and refrain from judgment.

So, you're saying not to judge?

— That's right. This applies to us both in wartime and before the full-scale invasion. We've been dealing with war for a long time. ... our reactions can be somewhat immature. We tend to rush to conclusions.

It could be a person who just doesn't talk. Yet, the person might have experienced things you can't even imagine. Or it might be someone who talks excessively. You realize you can't handle it, but for them, it's a lifeline. They use it to suppress fear and emotions.

Are they forgetting or repressing them?

— Repress them, probably, or rather, suppress them. In those moments, it's essential to be more considerate. Why? Because the other person may have such a history and trauma that it requires careful thought before jumping to conclusions. But it's difficult. I can definitely say it's difficult.

How have these internal changes influenced your artwork? What changes have occurred in your perception? I already understand that you've come to appreciate combinations you might not have attempted before due to classical education or other biases. Your perception has broadened now. So when I look at... tracing paper, these drawings on tracing paper are semi-transparent...

— I can say with certainty that I've stopped being afraid. People have come to see me as an artist who works exclusively with watercolors on canvas, or someone very ethereal, an air-painter. But I've enjoyed experimenting so much, and I've ceased to be afraid of how I'll be perceived. It's incredible, you wouldn't believe how liberating it is because you become free. And that's very important. Not only for statehood but for personal life as well.

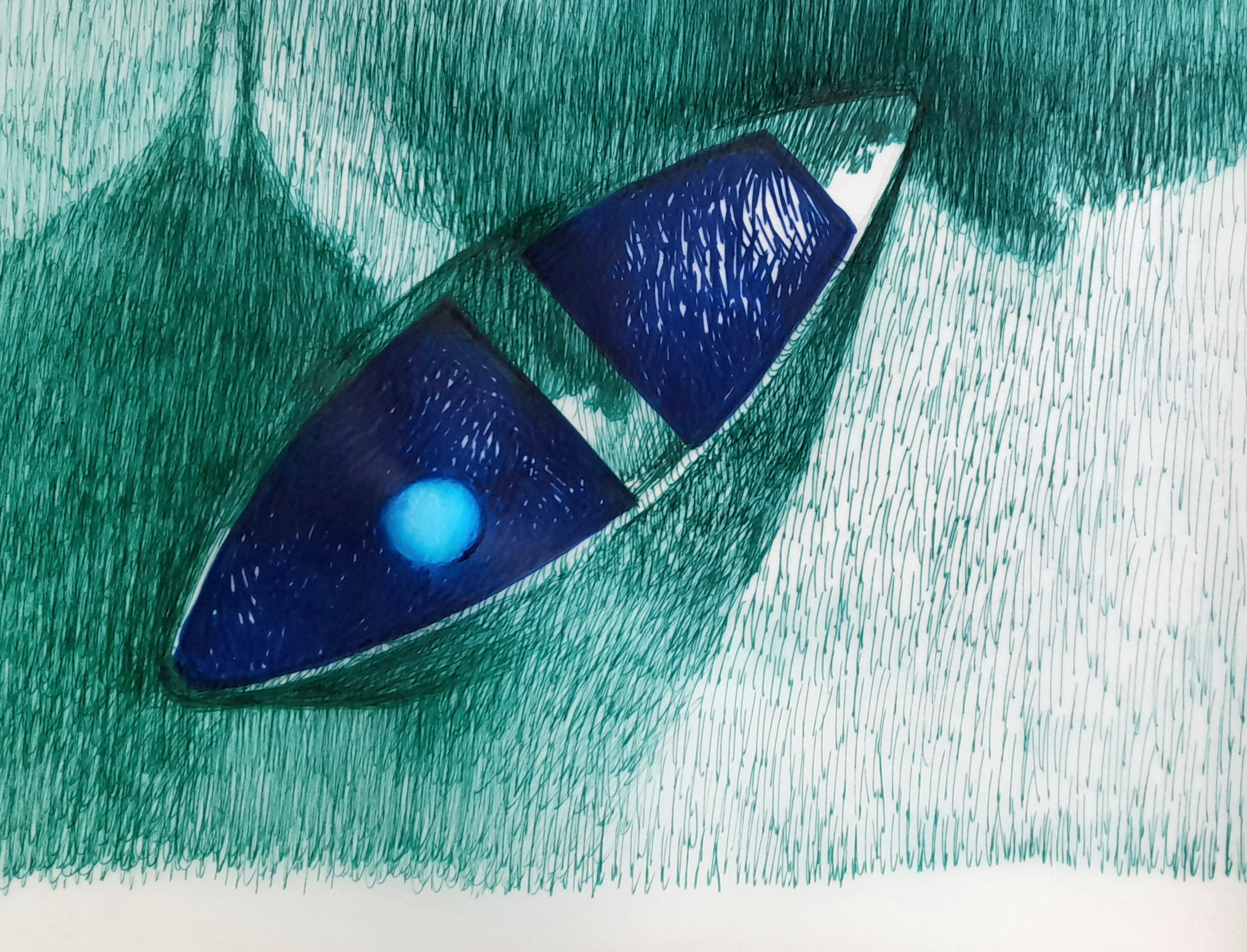

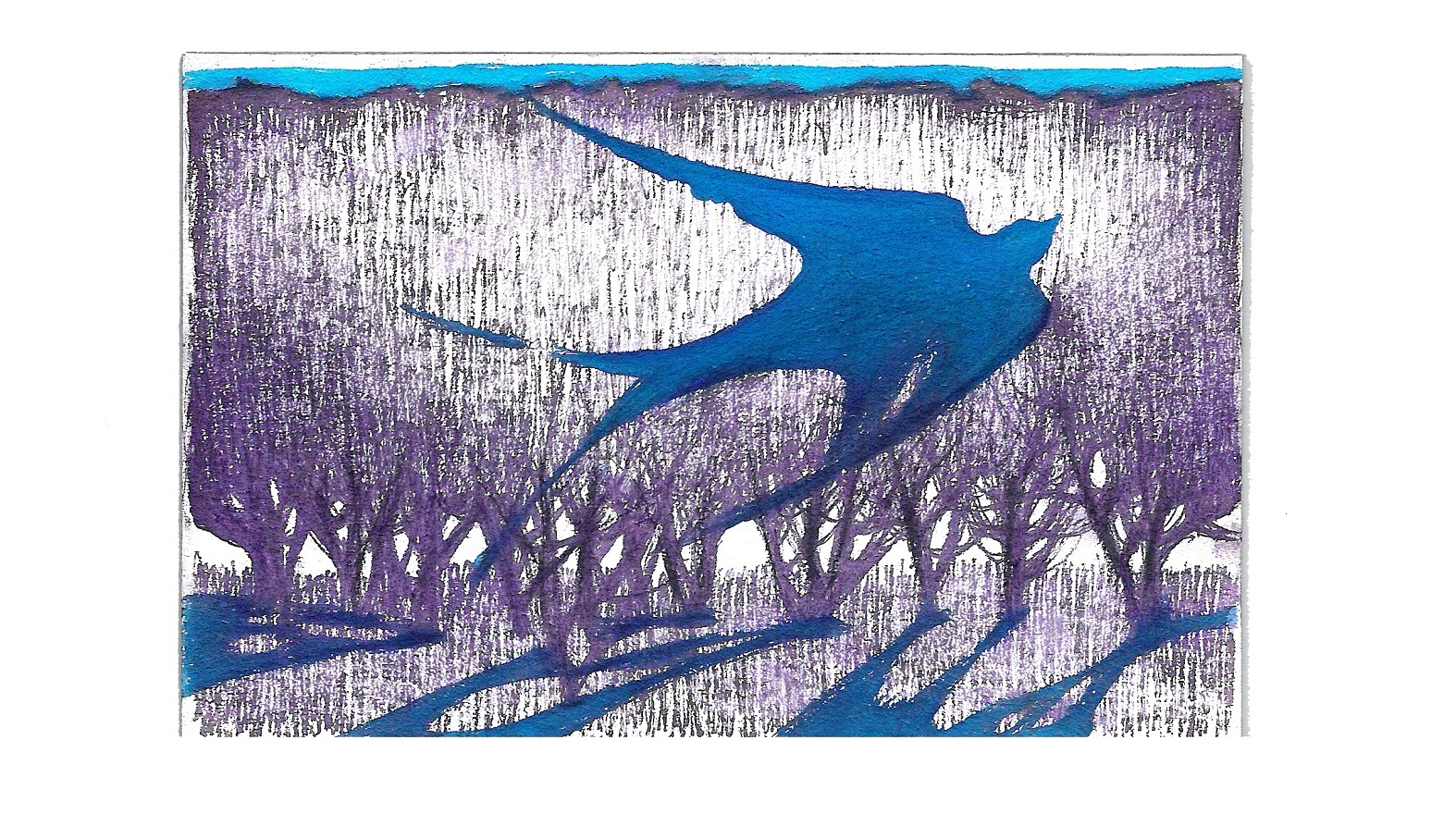

The reason I appreciated tracing paper is that in my latest project, it symbolizes layers and transparency. It conveys a lot about us, probably about our experiences and personal histories. You can perceive one story, maybe even several stories. You might see a bird, but you might not discern the numerous tales hidden behind that bird. What might be a boat, what might involve weaving, what other stories could be woven into it. This combination appeared very relatable to us because we often see what our eyes show us, but we don't always observe with our hearts, and we don't always see beyond. This tracing paper makes us more translucent, not just to ourselves but also in terms of communication. And that's of great importance. It represents a kind of tenderness that is perceived at an entirely different level.

In this drawing, I would interpret it as a blue bird. And I'm aware of your involvement in the "Blue Bird" libretto project. Let's discuss that for a moment because "Blue Bird" has become especially relevant to me now. For me, it's about the search for happiness, the quest for one's place, and even the exploration of one's role in a grand shared history where you're seeking roots, right? And I noticed a significant amount of vegetation in your work.

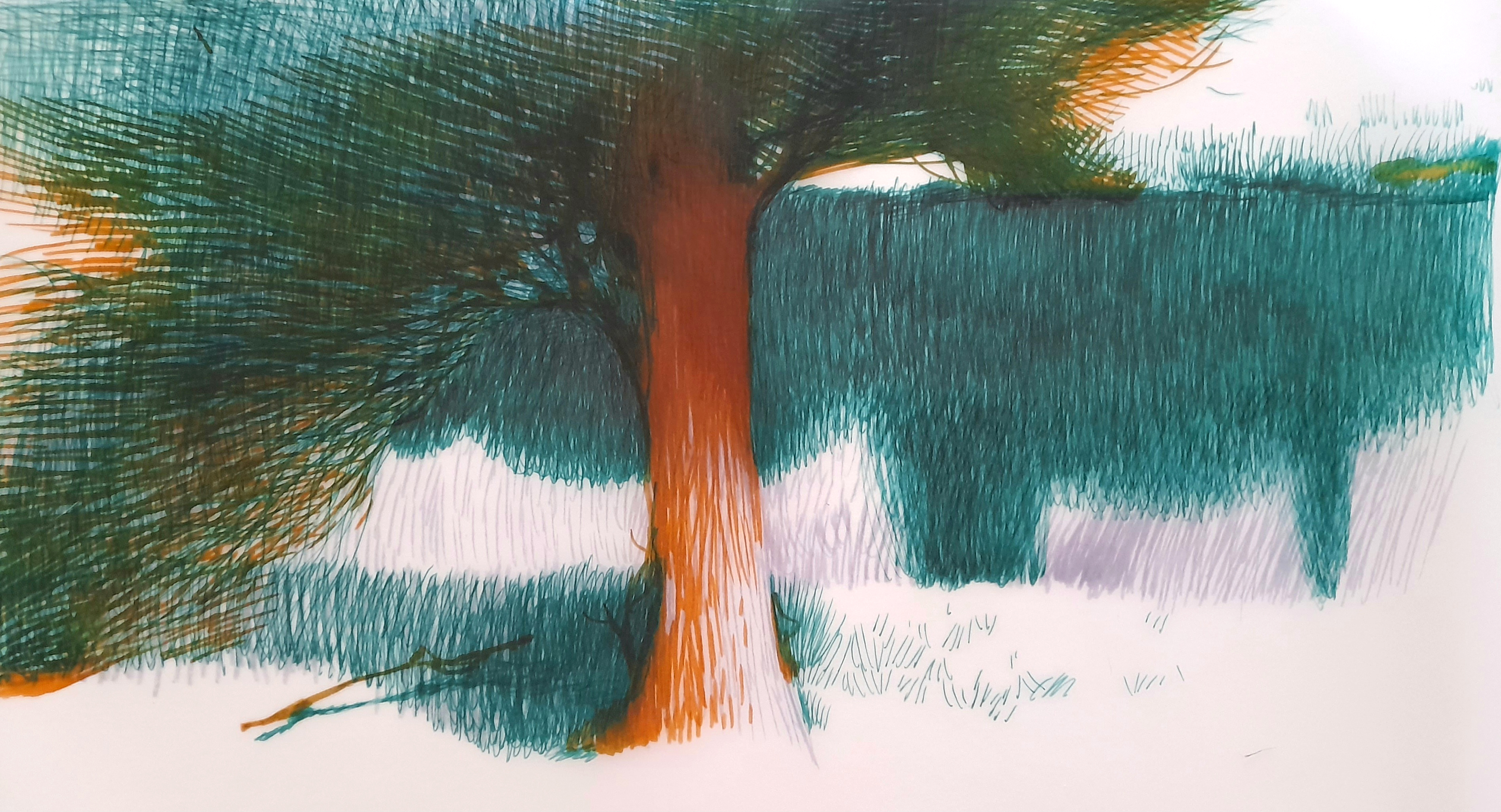

— Yes, that's true. In "Blue Bird," we discuss not only dreams and exploration but also the concept of sprouting. It seems that losing something is intrinsic to us as well. It's not just what we've lost; it's more like a forgotten dream. We need to restore it, to bring it back when discussing memory; it must be rebuilt and reborn. It's similar to the way trees grow and even to boats. You see what's on the surface, but the roots, they're all intertwined.

Any gardener knows that if you water a tree too close to its roots, you're not actually watering the roots. You need to understand how far you should step back from the tree to water it properly.

Water the roots.

— Yes, and this is where we often fall short, lacking the necessary distance from certain processes. We tend to approach things in rigid, categorical ways. 'Blue Bird,' however, embodies a blend of growth and return. So, when people asked me why I stayed during the spring, why I didn't leave, the first thought that came to mind was that it's impossible to kill or lose because it's more than just a home; it's more than just walls—it's like air, intertwining like roots. This intertwining represents not just ethnicity but lineage as well, and it holds you. Each tree sprouts within you. You can embrace it within yourself and become your own gardener. You'll learn when to nurture, when to be patient, and when the trees need sun, wind, and rain. These states are normal, not to be feared; they should be embraced.

In war, we often find ourselves experiencing these states, sometimes too frequently.

Our souls change.

— Yes, it's a spontaneous transformation, happening at a swift and unceasing pace, much like the flow of time. To avoid losing this precious time, we mustn't merely recreate it through touch; instead, we must learn to connect with the rain, the sun, the tree. When we're rigid and categorical, we lack the time for contemplation and listening; we process everything too swiftly. It's a journey of self-awareness, an intricate story. Yet, amid the breakneck speed of life, stopping becomes a necessity to survive, an opportunity to pause.

Recently, someone asked me about this following an instance of shelling, and I found myself in such a situation. The strength of the moment was compelling, but what truly halted me was standing beside a river, observing a white bird that remained perfectly still. It continued its routine, preening its feathers, waiting, searching for something. And I, too, stopped. In the midst of a world moving at a frenetic pace, I paused. This image has lingered in my thoughts over the past two day—the serene, unmoving white bird on our river.

Returning to 'Blue Bird' and the metaphors we've been exploring, it's already an intricately metaphorical story. There's a moment in the story when Brother Til falls into a coma, embarking on a journey to discover his own family and search for his roots. The entire narrative unfolds within this coma, and when he awakens, he carries this profound experience with him. So, considering everything we've discussed, the question arises: Do we, too, need to awaken? Will we awaken?

— The answer is a resounding 'yes.' This process is ongoing. It's happening continuously. In fact, it's always unfolding around us. Sometimes we're keenly aware of it, while at other times, it escapes our notice. There are moments when we require not only distance from others but also a deep introspective look at ourselves. We must recognize our personal history as an integral part of it. This perspective is remarkably important, much like the story of the boat. You become not just an observer of what surrounds the boat; you are the boat itself. It's about steering and propelling it. It's a vessel that carries the vast sky within.

Speaking of 'Blue Bird,' did you create the drawings for the project, which, I believe, began back in 2018?

— It's the same 'Blue Bird': 'The Return,' and there was also the original 'Blue Bird,' but in a full-scale format. You might wonder about 'The Return'—it's particularly close to my heart because the original 'Blue Bird' was very ethereal, primarily in watercolors. However, this 'Blue Bird' has taken on a bit of weaving. Why, you ask? Well, back then, it moved like air and water. It was more of a philosophical tale, a serene one. But when I now speak of 'The Return,' I believe this 'Blue Bird' comprehends what a coma truly is. You return, but you leave behind the lightness. This lightness is like a thread, similar to embroidery. It's a continuous process, an action that brings comfort, perhaps.

It doesn't break, right? You also mentioned the notion that we are a part of time. This realization, for me, is the very reason we didn't leave. Because, logically, we probably should have left, right? But when you depart from here, especially to go abroad, you just cease to be a part of time.

— I left during the summer, but it was for an artist's residency in Poland. I was away from the city for just 14 days, and I remember every one of them. I understand that it's necessary. Many times, my friends in Germany and Austria offered to have me take a month off and then return, but I calmly replied that I don't see that as an option for myself. This is my personal experience and choice.

I've been involved in various projects, such as creating murals in hospitals, among other things. I also had students in the city whom I worked with, and some of these young individuals remained in Staltivka. [They didn't leave either.

Are you still teaching?

— Yes, I'm still teaching. My schedule is more flexible now as I've begun my doctoral studies in Toruń, Poland. I'm going to focus on a project related to Kharkiv.

Tell me more about this project, as we touched upon it briefly before the interview, and it piqued my interest, particularly the aspect of gentleness.

— I truly aspire to develop a multi-faceted project. My doctoral project revolves around Kharkiv, but it explores a different facet of the city – something we sense and experience but isn't about us.

So, if I understand correctly, it's not about invincibility?

— Exactly, it's not about being impervious. We're not composed of metal or structured like buildings. We're very vulnerable, incredibly fragile, and it's genuinely difficult and frightening for us. This is entirely normal; we all go through this. What's remarkable is that we can acknowledge it to ourselves and coexist with this vulnerability. Regarding fear, I always find it surprising when someone claims, 'I'm not afraid.' We all have fears, you know? It's just that some individuals can manage them and take action. You can either be afraid and do nothing, or be afraid and work through it.

Or you can choose to suppress what we've discussed, these emotions, and continue on as if you're not afraid.

— Yes, closing the drawer, and then this drawer just detonates, I would say, and that's the end of it. This project, in essence... To me, it's crucial to provide things with names. But it's not just about labeling emotions. It's about understanding who you are and how you live with those emotions. So, concerning Kharkiv, I give names to the river, to the trees, and to everything that surrounds me, everything that breathes life into this city for me.

How did you come up with the title...?

— "Step by Step," that's the title of the project. Initially, we named it "A Time of Long Shadows" because it resonated with the Poles, who perceive us as resilient people with a long and storied military history, akin to enduring shadows. So, it symbolizes a time of long shadows, capturing what's unfolding within us.

How will the project be presented overall? And why do you believe it will captivate people's interest?

— It will be incredibly fascinating because I already executed something similar last summer.

Did people express interest in it?

— Yes, the Poles expressed significant interest because I initiated it from my humble drawings, which was my starting point. The exhibition will be housed in a dedicated multi-story venue. On each floor, you'll find a step-by-step narrative — my daily sketches. It's going to be akin to a map of emotions, with entire walls dedicated to stories, reaching heights of over five meters, given that I may have up to three thousand drawings by that time. The initial story portrays a journey through emotions, step by step, encompassing each day you live. It's centered on Kharkiv — a Kharkiv that's as personal as can be, as we perceive the city through individual stories, unique trees, and distinct windows.

There will also be a separate space with only a single book. It will be an enclosed room illuminated solely by the light of one book. To me, this is the "book of the red thread," an art book. It's created from a single woven line — I'm weaving, weaving a home. It will represent a home-tree that unfolds into an individual story-book. This book has grown organically and continues to grow, like a tree.

The third part will involve Morse code. I find it quite intriguing to blend technical elements with visual and metaphorical components.These will be represented by circles and dashes, coupled with watercolor on canvas, encoded in a specific manner, akin to Morse code, each with unique meanings. These words breathe life into the city for me. It's imperative that we learn to communicate through our own experiences. We're frequently filled with anxiety, and those who aren't in a similar state as us may want to assist and understand. It's essential to determine how we convey our experiences to them and in what language. Thus, this project will be a dialogue with the Poles, but a dialogue about Kharkiv, a city that lives in various dimensions.

Yes, it seems as though we're drawing this conversation to a close, but I have two more questions. Our discussion has been deeply metaphorical. Could you tell me if the libretto is complete?

— Yes, the libretto is complete, and this is where the idea of layers and overlays really came to life. These layers are linked to the entire project, and it's not only about the memories of time, dreams, miracles, and other things; it encompasses the brighter aspects. These layers are at work, allowing you to see more than you might initially realize. It's about piecing together fragments of time. This is the essence of "The Blue Bird: Return" – a return to gather the fragments.

And to anticipate the publication, to revisit your works.

— The designer, Dina Chmuzh, did a fantastic job. We had in-depth discussions about her preferred style and my approach. However, our collaborative work managed to strike a balance, with some parts reflecting my ideas more strongly and others hers, but these drawings with overlays. It's truly remarkable to illustrate that each person has their own unique perception of time. When you collaborate as a team, it's akin to constructing a mosaic of time.

Working with the perspective of that individual.

— Yes, exactly. This mosaic comes together when you comprehend the individual, grasp the concept of time, and also understand your role in the project. You recognize that there are artists, designers, and project creators, each with their distinct viewpoints. So, how do you assemble this mosaic? It was assembled through the interplay of these layers, allowing each of us to contribute a unique story.

I'd like to express my heartfelt gratitude for this conversation; it has been therapeutic for me, and I hope, for those who will watch it. Thank you, and I wish for all of us to remember that we are indeed fragile.

— And not to fear it.

Yes, to recognize it and take good care of ourselves.

Translated from Ukrainian by Anna Petelina

Daria Khrisanfova, artist, and teacher of KhNUMY University named after Beketova

Natalya Kurdyukova, journalist, head of Kharkiv Media Hub