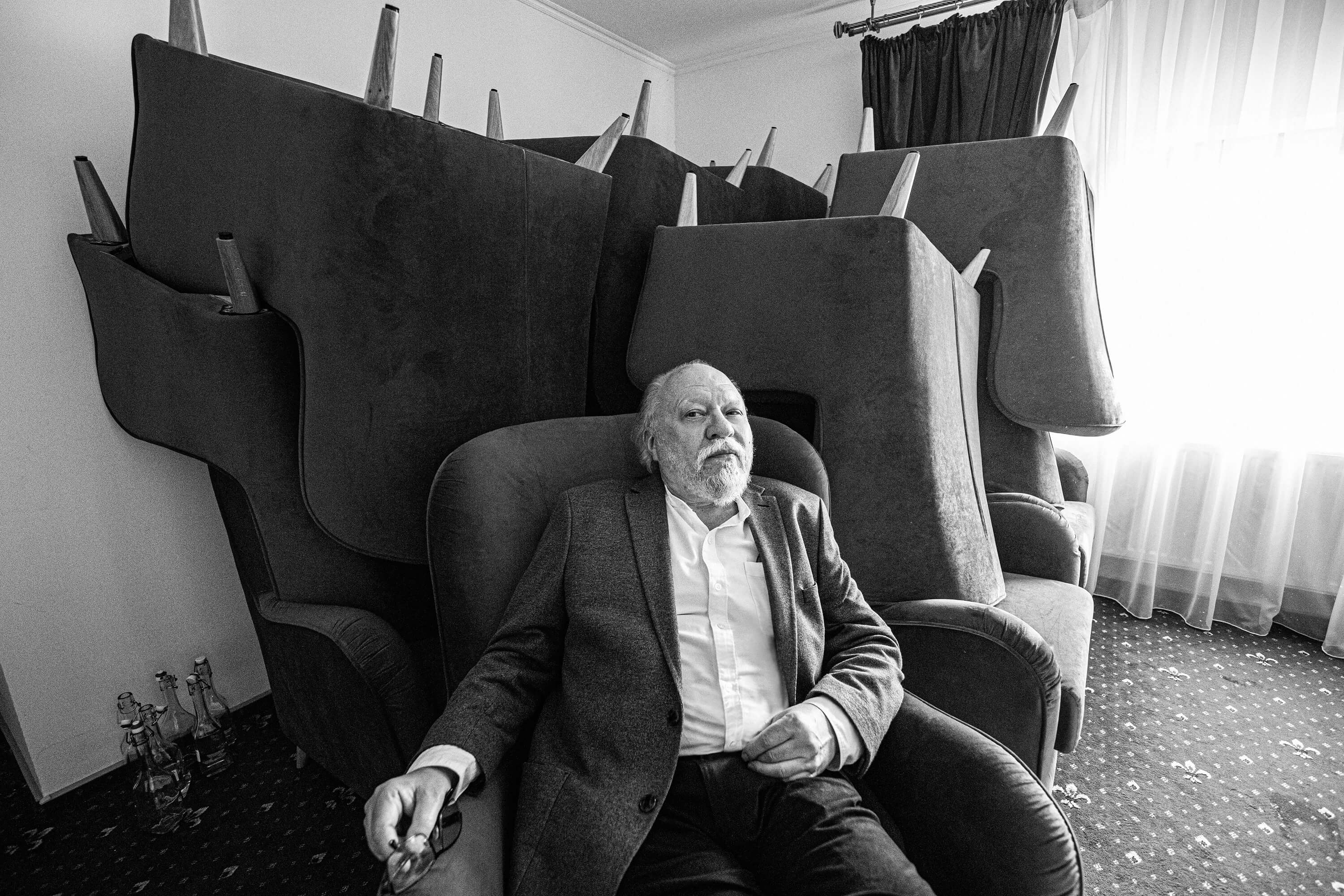

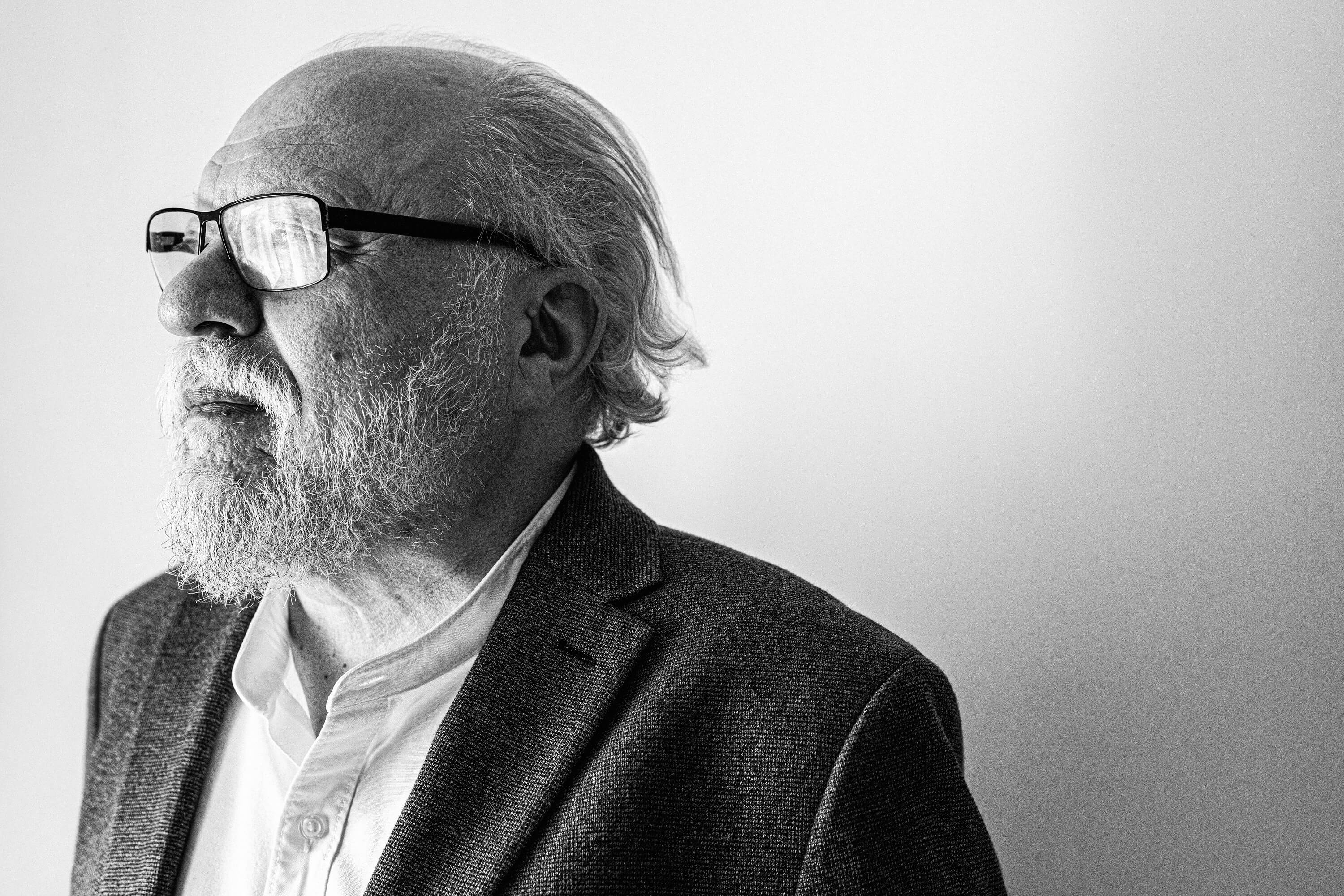

Igor Pomerantsev is a poet, novelist, essayist, radio playwrighter, editor and presenter of the Over Barriers radio magazine, journalist, Soviet dissident, wine critic. Author of the books Red Dry, Radio "S", KGB and Other Poems, Wine Shops, Homo Eroticus, Vilniy Prostir, and others. Winner of a series of prestigious awards in literature and journalism.

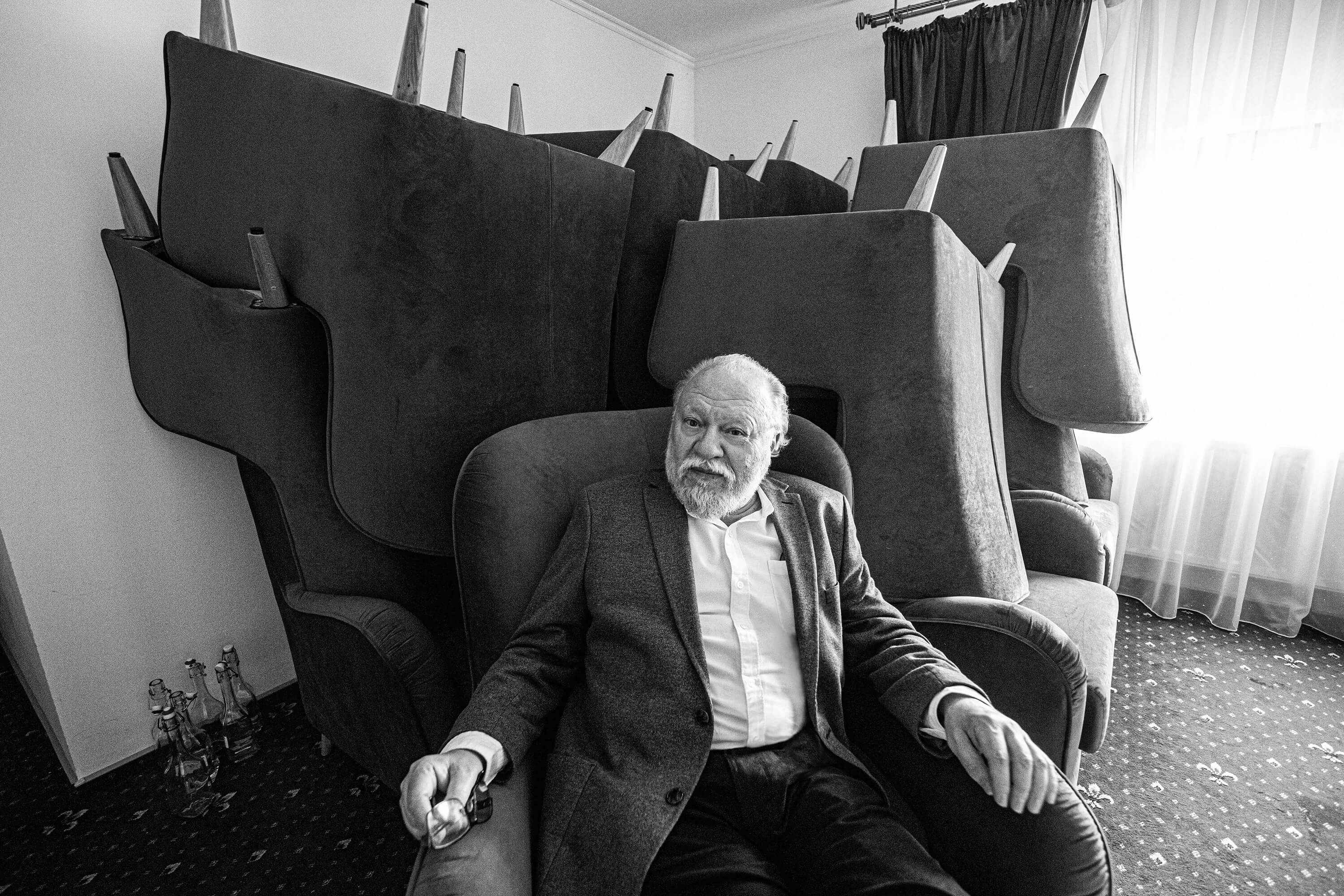

You have a closed pose on your main Facebook photo. You are sitting almost like a Rodin Thinker. Even yesterday, at a street presentation (the interview took place during the Meridian Czernowitz festival), you covered your face a little with your hand. Is your closed posture a defensive reaction or a brand image?

— I think psychologists or psychoanalysts would say better about this. Once a psychoanalyst looked at my photo — I was captured with my fingers clenched and especially hiding my thumb — and the analyst told me, “This is evidence that you strive to be a closed snail”. My place is a studio, and that's why I work on the radio. Nobody sees me; I want to be alone with my own voice. For example, I avoid live broadcasts and interactions. I like the cosmic capsule of a closed space, which I open with my own voice. At the same time, I do not see the reaction of the listeners. I don’t know if they point a finger at me, or think that l am nuts, or laugh. I would just prefer them to laugh. You know, there is a certain kind of laughter. Alexander Blok drew attention to this: when he read tragic poems about drunkards with the eyes of rabbits, people laughed. This is a nervous, emotional reaction. It replaces bewilderment. Laughter is next to death, even in the [Ukrainian language] dictionary. There are such cultures where death should be accompanied by laughter. There is such a concept in social psychology: an introvert in the role of an extrovert. This is my case. On the other hand, I am a public person. I understand perfectly well that the listener is real. I publish what I write — essays and poems. Therefore, I cannot be called a modest person. As a poet, I have an illusion: what excites me, should excite others. I am offering readers something that is vital to me, and I have the illusion that it is also vital for someone else. Graphomaniacs have the same logic as non-graphomaniacs. This is how it looks in theory.

I don’t really like to talk about myself. I have done programs with many outstanding thinkers and writers, for example, with Alexander Pyatigorsky. We never spoke about his philosophy, and we always chose topics tangentially. It could be Socrates or it could be a “non-Russian idea”, and in this field, he expressed himself as a philosopher. He never spoke about himself directly. Therefore, it is difficult for me to imagine my self-portrait. I once found a definition for my poetry: a bat, pointed at by a flashlight. I am this bat. I prefer attics and basements, and then, suddenly, I remember that a rodent can and wants to fly. It is a difficult feeling — on the one hand, you want to hide somewhere in a nook or a dark corner, but on the other hand, you still want to be seen. Therefore, we will focus on the image of a bat, especially since in connection with the pandemic it is seen as a truly sinister creature. But you can be sinister and attractive at the same time.

A very important question for me: is it possible to equate the concepts of emigrant and displaced persons? What do they have in common and what is different?

— A displaced person is a person who migrates within the framework of their culture and their language, as a rule. Therefore, that person needs to adapt to the new city, yes, but within the framework of common culture. Emigrants ... emigrants are different. Every person has the right to emigrate. There are political reasons; there are economic ones. Here I am more interested not in my own particular case, but how the concept of "home" has changed in the twentieth century. That was the age of the most brutal political and social experiments. For example, Stalin solved the housing problem in The Soviet Union very simply. He built a huge GULAG system. Millions of people just settled in the barracks. Hitler also solved a number of housing issues, when millions of people were not just evicted, but destroyed. I'm talking about the Holocaust. Later, when the revolutionary lava slowed down, communal apartments appeared in The Soviet Union. People were supposed to live on top of each other, people were supposed to be friends because of the socialist idea, but instead, they began to hate each other even more. In the twentieth century, the concept of a home radically changed. A huge number of people appeared who could be called emigrants, or they could be called displaced persons. This concept is legal. It arose after the Second World War, and we are talking here about millions of people. Displaced persons fled to North America and to South America. Among them were, for example, war criminals. There were a huge number of all kinds of people. And among them were people close to me — political emigrants. But I feel close to both refugees and defectors. This is my nation. This means that I have compatriots; it means that I have a homeland. Here it is, my homeland! Anna Akhmatova once wrote with disgust about emigrants. Well, she did not like them. And I say with pride, “This is my family: migrants, refugees, stray dogs of Europe.”

To some extent, your emigration was also forced ...

— They often and aggressively breathed on the back of my head, let's say. I had a conflict with the state. The state in this conflict was represented by the KGB. I was a young writer and wanted to read what I was interested in, and to write what I was interested in. I wanted to speak out. And it turned out that I was reading forbidden books, and this reading threatened my freedom. This was discussed during interrogations, and I was advised to leave The Soviet Union as soon as possible.

I read that in emigration you began to speak Ukrainian. Is that true?

— I knew Ukrainian because I loved it. As a child, I read hundreds of books in Ukrainian, mostly adventure and science fiction. At school, I had a solid ‘B’ in the Ukrainian language. This laid the foundation. And it turned out that my ‘B’ is worth something. I was invited to speak in Munich at the Ukrainian Free University and give a lecture on underground Ukrainian culture in the USSR, and, of course, they expected me to speak Ukrainian. I was delighted to speak Ukrainian. These luxurious rolls of Ukrainian words were in my mouth as if I was participating in a kind of linguistic adventure. My love affair with the language began. Our love was mutual. This love also had a practical streak. My first contacts in emigration were not with Russian political emigrants, but with Ukrainian ones. I received my first invitation to speak on Radio Liberty in Munich from the Ukrainian editorial office. For the first time, I went on the air not in Russian, but in Ukrainian. I wrote several short essays in Ukrainian, and my editor, the outstanding Ukrainian poet Igor Kachurovsky, did not make any edits at the time. But I wrote about poetry. It was a small essay "Zamovchana Poeziya" about the Kyiv School of Poetry. There was a very significant phenomenon in Ukrainian literature, which was hushed up in the Soviet Union.

Is poetry an opportunity to unwind a tangle of culture or, on the contrary, to rewind it, weaving your biography, impressions, and worldview into it?

— Poetry is a fluid concept. The point is just to re-name it differently each time. In addition, poetry has many different functions: there are the concepts of "cultural memory", and "historical memory". There is, of course, historical research itself, but poetry is the memory of language. Without poetry, language would become limp, it would lose its own memory. It's not just humans that suffer from sclerosis. We learned poetry by heart at school. It was a classic, and there were a lot of words unfamiliar to children in it. This function is purely pedagogical, but it is very important. No matter how they say that at school they discourage a taste for literature, a child, in principle, cannot perceive poetry and literature as a mature person can. Therefore, children learn to understand poetry on the street, with the help of dirty couplets. A thug song, such a romanticization, is also good for these purposes, right? The fecal theme works very well in childhood because at this time a person still has a fresh memory of their physiological state. When diapers are changed, the child does not consciously remember this, but it remains in their physical memory. Therefore, fecal poems are well remembered, and thanks to them, the child begins to understand what poetry is because poetry has to touch you.

Does this educational structure find expression in Russian chanson and rap, primitive pop, and other rustic cultural formats?

— You're right because most people remain infantile when it comes to artistic taste. We are now in Chernivtsi. I grew up here. As a child, I was a real movie lover. At 10 am, the screenings began at the Zhovten cinema, and I was already waiting at the entrance. I watched mostly adventure films: The Three Musketeers, The Iron Mask, Fantomas. And later I thought, “I was the only child in the cinema. Everyone else was an adult.” They are still sitting in this cinema. That is the mystery. If it occurred to me now to revise The Iron Mask, that would be a pragmatic intention. For example, to remember some frames for a story, and childhood memories. But all these people are still watching The Iron Mask. They were, are, and will be infantile. Therefore, poetry is the chamber. This is its dignity, but this is also its weakness — in the absence of a broad resonance. But it, on the other hand, does not need a wide resonance, because the poet writes alone with himself. And he imagines not readers, but a single reader. Yes, poetry is vulnerable in a social sense, but artistic power helps it out.

Is there a lot of physiology in poetry?

— It depends on the poet. It is individual. There are poets who have an ideal combination of physics and metaphysics. There was even such a school of poetry in Elizabethan England. Its main representative was John Donne. It's not just about physiology and metaphysics. It's about vocabulary first of all. English poetry has its own nervous system; Ukrainian poetry has its own. The meaning of Ukrainian poetry is to let the language survive. It has lasted about three hundred years, and this is the existential power of Ukrainian poetry. The language needed to survive, and it survived thanks to poetry! And the nerve of English poetry lies in the alternation and opposition of Anglo-Saxon soil vocabulary and Latin roots. Forty percent of Latin roots were brought into English through the Normans and French. This is a huge number. Almost all abstract concepts in English are expressed in Latin words. And the nerve of English poetry, its intrigue, is in how the dominant alternates — whether Anglo-Saxon or Franco-Latin words win. In the work of the Elizabethan people, these two elements found their harmony. Especially in the works of John Donne. He could write about the flea as a carrier of carnal love: bite, blood, and lovers’ blood exchange. And yet he was a metaphysician. He saw the Creator's idea behind everyday phenomena. Take the eye, for example. The function of the eye is to see. But the eyes are also the opening of you by the world, and the opening of the world by you. This is very important to understand for everyone who works with words, whether it is radio or literature. Even on the radio, simple things, news, for example — people listen to it eagerly, which means that a person is curious. Or here's an interview. Well, we talked, right? But this interview shows that people are able to talk, enter into a dialogue, that they are open, and they learn something new about each other. Or, for example, the genre of polemics: people are ready to fight to the death for their views because “polemic” is translated from Greek as “war”. Therefore, even when we talk about journalistic genres — all the same, they have their own metaphysics and their own philosophy.

What makes people not only hear the radio, but rather listen to it?

— It's a wordplay. It is known who mostly listens to us. These are the housewives at the ironing board. This is a very meaningful pastime. On the one hand, you are doing a good thing for the family. On the other hand, you are getting to know something new. Then, artists listen to us a lot when they paint their canvases. The hand is moving and the ears are on. The artist and writer Inna Lesovaya once wrote to me. She lost her sight at about thirty years old. She wrote to me, "Don't forget that radio is the favorite art of the blind." These are the target audiences. But there are also people who listen to specific programs. For example, I really love BBC3, classical music, jazz, and sometimes very sophisticated prose. I especially love BBC3 because I collaborated with it, and my stories aired there. The outstanding actor Ronald Pickup read them. He chose these stories himself. He is best known for his role as Orwell on television. For me, a special reason to be proud — Samuel Beckett chose Pickup to read his stories. This is the connection. Beckett chose Pickup; Pickup chose me. BBC3 and BBC4 are radio stations for people with secondary and higher education. Radio is for people who understand music on the one hand and understand complex sentences on the other hand. Most people prefer simple, common sentences.

Has Ukrainian vodka culture switched into wine culture? And was it ever vodka culture?

— We are moving into the zone of assumptions and profanities. I don't think I can fully answer this question. I understand the culture and art, yes, but I have been living in the West for a long time, and I don’t know Ukrainian subtleties. There are many excellent Ukrainian analysts who understand the issue better than I do. The only thing I can say that I see when I’m visiting Ukraine is a movement forward, a movement towards Europe. And the people of culture, those with whom I communicate and work have long been citizens of the European Union, and I, as a British, found myself thrown out of the European Union. Life is unpredictable! My British passport, once one of the most powerful documents in the world, is now having major issues. Now, for example, I cannot live in a European country for more than 90 days, neither in Austria nor in France, but I still dream of completing my not only etheric path in Trieste. It would be an interesting trajectory. I grew up in Chernivtsi, at the intersection of cultures, in the former Austria-Hungary. I have been living in Prague for twenty years, this is also the former Austria-Hungary, and I wanted to complete my life in the south of the former empire, on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. I wanted to buy a small house there, live against the background of the German language interspersed with Italian and various Slavic languages, but now these dreams are smashed to smithereens.

Maybe the British will come to their senses?

— In any case, we will live among the shards of empires.

How long does it take until the feet wean themselves from the broken asphalt and get used to the smooth one?

— It happens very quickly. I remember my German friend, a writer, was invited to perform in Romania, and he broke his leg on the very first day. He was not used to potholes. I also stumbled twice in Chernivtsi.

Your books are like a wine blend. These are not just collections of poems, these are essays, notes, and prose under one cover ...

— I really am a genre deserter. It is my choice. Over the years, writers begin to repeat themselves. I once interviewed the classics — Dürrenmatt (classic of Swiss literature, playwright, and writer), and Lawrence Darrell (English writer, brother of Gerald Darrell). I asked them if they were afraid of self-repetition? They answered, ”We can only write, nothing else.” I think, in this case, the writer has the right to be cunning. As soon as his hand starts to draw letters automatically, it is better for him to change the genre for the risk. In a sense, this is my strategy. I don't want to be like myself. Look, the classics of the twentieth century, for example, Graham Greene (English writer, intelligence officer, author of action-packed novels) or Lawrence Darrell, they wrote worse and worse over the years. It's still an Anglo-Saxon school. It's always above par. However, their later novels are worse than those they wrote in their younger years. This is an example of what not to do. Therefore, when I feel that the optics are blurry, I write almost automatically, and I have a set of copyright clichés, I go to another zone where I take risks. When you take risks, you rediscover both literature and yourself. But the risk is associated with the fact that the reader may not appreciate this and may not understand. The readers are conservative. They expect from you what you were able to do before. But here already — the reader is the reader, and the writer is the writer. But a talented reader will understand and accept everything. This is so in life as well — we often live by inertia. I'm talking about the automatism of life first of all. The same well, the same bucket. A writer always has what is called style, but this can also be called a set of techniques. I chose this strategy for myself — traveling through genres. And where there is a journey, there is an adventure; where there is an adventure, there is a fantasy. For me, this is a justified risk.

Tell us about the genre of the interview. You are a person with vast experience in this genre. What is its specificity, what is its subtlety?

— There are different craft tactics for interviews. There are journalists who count on their charm. I am not counting on it. I always prepare. I carry out the so-called research, making up a range of questions. But I also leave room for improvisation. The interviewee appreciates when the interviewer prepares for the conversation. The worst thing is to start by asking, "Tell us about yourself." This is very boring, this is objective, and the interviewer has to prepare this on his own. And the interviewee needs to be completely personal. The main thing is to have a conversation, but there is no exact recipe here. There are journalists who like to provoke their interviewees. They prepare like me, but they ask tough questions. If you agreed to be interviewed, if you are a public figure, you must be ready for any reaction. If the question is unpleasant, you can not answer it. Some react nervously, rip off the microphone, and leave. I think this is a sign of weakness. We are all different. There are, for example, irresistible women interviewers, they can get away with literally everything (laughs).

You spoke at the creative meeting about Osip Turyansky. He wrote the Ukrainian story "Beyond the Pain" actually from within the First World War. The prose of Hemingway and Remarque was also written with distance. Do you think a writer should describe a war immediately, in fact, or should he take a break for reflection?

— It all depends on the author's temperament and the genre. Poetry is spontaneous. Poetry captures the state of a person and the state of language in sync with events. Remarque wrote the novel ten years after the war. Richard Aldington (English poet, writer, referring to the novel Death of a Hero), Robert Graves (English poet, literary theorist, writer, referring to the novel Good-Bye to All Tha") are Englishmen who wrote about the First World War, — also after about ten years. If we return to poetry, then it merges in a paradoxical way with the art of reportage. I often cite the example of English trench poets (young English poets who participated in the First World War: Rupert Brook, Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, Julian Grennwell and others), many of them died on the frontlines. It was them who put an end to the tradition of admiration for war and glorification of war. They moved away from the pathos that originated in Homer and then found development in Charles Peguy (French poet, monarchist, conservative) and Kipling. They found new vocabulary and new images; poems about how rats run between corpses. These poems are made of lumps of dirt, blood, urine, and sweat. It was a shock for the Georgians (a cultural generation in Britain of the 1910s), a discovery of a topic, and a discovery of vocabulary. I often think of Wilfred Owen's wonderful poem “The Sentinel”. A sentry rushes into the bunker. He is wounded, and he has lost his sight, and he screams “I don't see anything”. A comrade runs up to him with a candle, “See? See?” “No, I don't see anything”, he replies. Then another bombing, everyone is dead, and suddenly the blind man screams, “I see the lights”, which means that he is completely blind. It was a literary feat: to find new optics and new vocabulary for this meat grinder. This is due to the fact that the war has lost its individual properties and has become total. Automatic weapons have appeared, and other military mechanisms have appeared.

Now we also live in a world war with coronavirus. This is a new war, a new format of war. This is a war where there is no front or rear, where we are all vulnerable, and where we are infantrymen, prisoners, and hostages at once. I wrote a poetic cycle "Immune Response", which describes our current state. My son was ill in the first wave of coronavirus. We were all very worried. And I myself am at risk. This is a special state. You react very sensitively to everything. You are looking for death statistics. Have they found a new drug? I'm on the front lines. I completely, unexpectedly became a front-line poet.

So poetry is a reaction?

— Yes, poetry reacts spontaneously and synchronously. Prose takes time to happen. The memory of a prose writer and a poet are very different memories. The prose writer remembers events in their sequence, and the poet remembers associations. The poetic reaction is therefore faster and often more accurate.

Do you read modern Ukrainian literature about war? Can you highlight strong texts?

— I am gradually losing the ability to read because of my eyes. Therefore, it is difficult for me to judge. When you are young, you read everything. And in my mature years ... I remember the lines of Leonid Pervomaysky, "One gets close to a bus, it’s not enough for an hour." You are young, you probably don’t remember, in the seventies, you were taken to be buried on buses. The gray-silver buses went to the cemetery. In my childhood, coffins were taken away on carts. I even wrote a story about it "To the Music of Chopin". There is a boy. He lives in Chernivtsi not far from the cemetery. He has theatrical binoculars, and he watches. And this is a great theatrical event for him. He examines people, he examines the details of the ceremony. He was struck once that a boy like himself was lying in the coffin. So, in my youth, I had a lot of time to read books, but now the silver bus is approaching, and I have begun to save my time. I even use the research method for writing poetry, that is, search, research, preliminary work. I believe that a literary text should be interesting. This is an indispensable condition, and if you're lucky, then it can be talented. But to be interesting is a mandatory prerequisite.

If you were not born in The Soviet Union, but in a free country, and if you had not experienced ideological pressure in your youth, would you still have started traveling? Would you lead such a nomadic lifestyle as you do now?

— I've always loved travel books — so, yes, I would. Why I traveled so much is another matter. At some point, I realized that this is a form of geographic neurosis — an escape from something. This is not just a fun traveler with a backpack that walks through the Alps and the Sahara. This is a form of neurosis. And it's okay to indulge yourself. It sharpens your hearing and your eyesight. It's a job to travel. Now the journey has lost a little of its original meaning — "marching along the path", right? We travel by plane and do not feel traveling as a process. We have a goal, but we do not have the experience that Marco Polo had, for example. For years he drove, walked, remembered, then shared his impressions with others. But now there are conservative travelers, pilgrims, for example. They have a purpose, the journey is a form of spiritual growth for them. The planes took away a lot from us, but they also gave a lot in return. Many countries can be visited. Anyway, traveling by plane has become an analogue of time travel. You can fly to the nineteenth century. You can fly to a theocratic country and find yourself in the Middle Ages. Where there is a pro, there is a con, as they say. But I am not flattering myself. I realized that I do not like to discover new things. I like to rediscover old things, to return to where I have already been, and to feel something in a new way. We are now in Chernivtsi, and I listen to my city. I am very pleased with the spoken Ukrainian I hear. I do not know enough German, but here, at the festival, there are German poets. Sometimes I hear Romanian conversations. As a child, I was very fond of the Romanian language, not only on the street but also on the radio. Here they caught Romanian radiowaves. I was always fascinated by the broadcaster’s announcement “Ora exacta”. It seemed to me that this was the name of a beautiful girl, but then it turned out that it means “exact time”. When I was young, I wanted to take such a romantic pseudonym — Ora Exacta. What I miss in Chernivtsi is the Yiddish language. It was always in Chernivtsi. I remember my mother and I went to the market, and I heard wonderful conversations — a mixture of Yiddish and Hutsul dialect. Jewish ladies bargained with Hutsul peasant women and understood each other perfectly.

Tell us about your family — about your father, about your brother. You and him, I somewhat understand, are very different. Tell us about your son. What is the Pomerantsev family?

— I never thought about it. What is important to me? When we moved to Chernivtsi from Chita, from Transbaikalia, at the age of six I suddenly discovered that my parents communicate freely in a language I didn’t know. It was the Ukrainian language. My father also wrote in it fluently. He was a war correspondent during the war and then worked in the district newspaper of Transbaikalia until 1953. My father was from Odesa, so he could speak and write in Ukrainian. So for me, Ukrainian became almost a native language too. And I inherited my wine instinct from my father, through Odesa, and across the Mediterranean. It is also important for me that my mother is from Kharkiv. There is a specific Russian dialect there, with its own words. I knew the word "trempel" from childhood. Mother was wonderful at coming up with new words. My father was a professional journalist, he wrote mainly feuilletons. I remember the smell of ink, my father's back while working, and how he read aloud in Ukrainian. It was natural for me to sit over the paper and do something with it. We had a good pre-revolutionary library; my father was a book reader and collector. We had Hobbes, Spencer, Nietzsche, and a lot of great things. The library has not survived; they were not released into emigration with valuable books. Nevertheless, the smell of ink, the clatter of the typewriter, the library — I've gotten used to this since childhood. As for my brother, yes, one child in the family was an athlete, the other a poet. My brother also had a very sensitive attitude toward the word. He came up with many witty words but chose a different path. They predicted him to be the European champion in sambo and judo, but he turned out to be psychologically fragile. At twenty, he suddenly lost his insolence on the wrestling mat. He behaved like Hamlet, which is not the way in sports. You have to be cruel. The coach told him, "Valyok, you see, he has a bandage on his knee, hit under the bandage, he has an injury there!" My brother was not ready for this kind of fight. He was the champion of Ukraine and the youngest master of sports in Ukraine. When you achieve such success at a young age, you must either make a sharp leap in the other direction or you must withdraw and depression begins. He died early.

Is there one character trait inherent in all members of the Pomerantsev family?

— Of course not. We are all different people. But here's the thing: you know, there were professional guilds in the Middle Ages. You were born into a sewerage cleaner family, and you will be a sewerage cleaner; you were born into a weaver's family, and you will be a weaver. Closeness to the language remained. My nephew is not a writer, but he is the president of a literary festival. The Middle Ages have long passed, but elements of the medieval structure in some families have been preserved. My son is a British writer, my father is a journalist, and in Odesa someone from my clan was the author of a book about Odesa synagogues. So the Middle Ages passed, but people remained, and some traditions are still being passed on from generation to generation. My son is lucky that I am not a sewerage cleaner.

Translated from Ukrainian by Kateryna Kazimirova

Igor Pomerantsev is a poet, novelist, essayist, radio playwrighter, editor and presenter of the Over Barriers radio magazine, journalist, Soviet dissident, wine critic. Author of the books Red Dry, Radio "S", KGB and Other Poems, Wine Shops, Homo Eroticus, Vilniy Prostir, and others. Winner of a series of prestigious awards in literature and journalism.