Natalka Bilotserkivets is a Ukrainian poet and essayist. She has published six volumes of poetry and several editions of selected poems. The collections Allergy and Central Hotel were Books of the Year in 2000 and 2004, respectively. Her poetry has been translated into several languages (primarily English, Polish, German, and French), and distinguished with many national and international awards. The English translations include Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow, translated by Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky, published by Lost Horse Press (2021), and Subterranean Fire: The Selected Poetry Of Natalka Bilotserkivets, translated by multiple translators, published by Glagoslav Publications (2020-2022).

In recent years, Natalka Bilotserkivets has been writing prose, but after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, she returned to poetry.

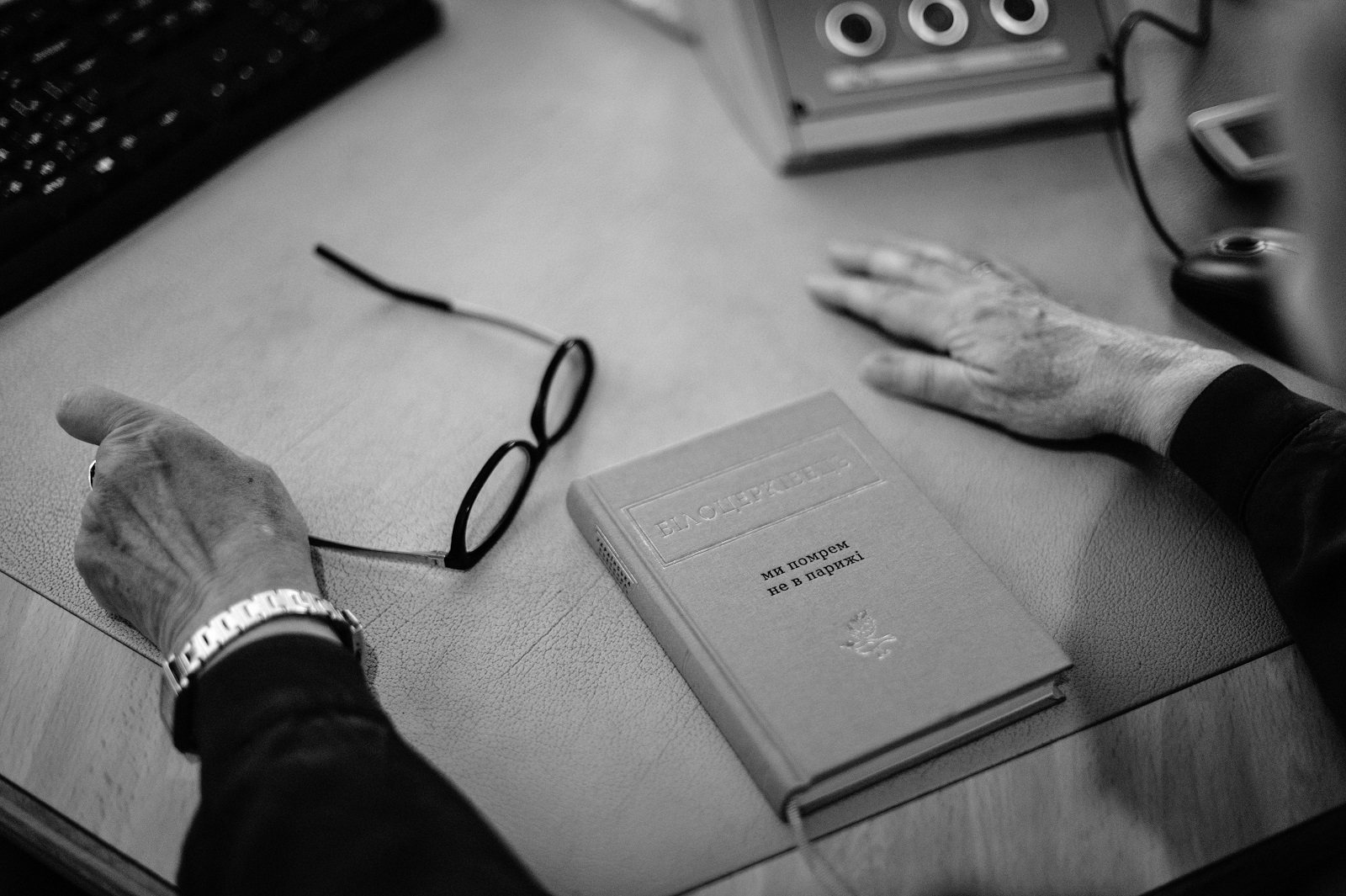

The official reason for our conversation was a new book of translations: Dzvinia Orlowsky and Ali Kinsella adapted the poetry of Natalka Bilotserkivets into English and put together a somewhat unique edition. If you have seen at least one anthology of Bilotserkivets’ poetry, you know that they are arranged chronologically by consecutive blocks from the author's various publications. (To date Bilotserkivets has published six books of poetry). Orlowsky and Kinsella organized Bilotserkivets' poems thematically and have written an intimate biography of a woman poet, from adolescent interests to the deep experience of mature love. Readers of Bilotserkivets' poetry already know how contrasting, sensuous, physical these works are—at the same time, they are overwhelming, but are written in halftones. The new book has sharpened all these qualities, shifting the emphasis from music to image, becoming so tense that it vibrates, bringing the author’s painful zones, heretofore hidden in her chronological approach, to the surface.

We began our conversation with Natalka Bilotserkivets with her "Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow" volume of poetry, and only later, carefully reflected on the poet’s emergent painful realms.

— Published by the American publishing house Lost Horse Press in the autumn of 2021, by the spring of 2022 Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow was already shortlisted for several prestigious awards, including the Griffin Poetry Prize and the Derek Walcott Prize for Poetry, which are awarded for poetry written and translated into English.

The book received an award from the American Association of Ukrainian Studies. From the very beginning, I considered this book to be a joint project with translators Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowska (and generally I regard translators to be co-authors of poetic works).

They select the poems, the composition of the book, and even the title. Ali and Dzvinia came up with— Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow—a title that remarkedly echoed that cruel spring of 2022 and could captivate both reviewers and jury members and compel them to read the poems themselves. Poems by a poet from Ukraine, a country where a great tragedy was unfolding during those eccentric days.

Do you encourage translators towards your own interpretations, or do you tend to agree with their translations of your work? You yourself have considerable translation experience. Your translations of Czesław Miłosz’s "The Body" or "At a certain age", for example, are clearly not random works.

— I have never thought of myself as an experienced translator. Translation is a professional matter. My translations are a kind of retelling, and I don't think they should be viewed as a model. The only possible exceptions are my translations of Miłosz’s late works. For me, Czeslaw Miłosz together with Tomas Gösta Tranströmer have become symbols of the great old poets, something that I would like to become for my younger readers. These poets have become profoundly penetrating in their radiant, courageous old age.

Anyone who translates poetry must determine for themselves what to focus on. Whether it is history or imagery, what is important is to recreate that focus accurately. In my texts the focus is music. Perhaps history is the easiest to convey, imagery is a bit more complicated, but music is the most difficult, and so many of my poems are first and foremost musical. It is good if the translator is a poet, or at least someone who at one time tried writing poetry and has some idea of subtleties and nuances. A translation need not be literal, but it is essential that a translated poem reads as if it was created in that language. Each language has its own music.

All poetry is a kind of artistic translation of human emotions, thoughts, lives. There are many such translations-allusions to other people's works in my poems. But I almost never make them explicit, my readers are well-read enough to understand these allusions. An example of such "postmodernism" is my poem "We will not die in Paris," which contains a direct reference, a motto from a sonnet by Cesar Vallejo. There are hidden intimations of two more great poets: Guillaume Apollinaire with his masterpiece "Mirabeau Bridge" and Paul Celan, who was born in Chernivtsi (Ukraine) and died in Paris, jumping into the Seine from the famous Pont Mirabeau.

we’ll not die in Paris I know now for sure

but in a sweat and tear-strained provincial bed

no one will serve us our cognac I know

we won’t be saved by kisses

under the Pont Mirabeau murky circles won’t fade(Translated by Dzvinia Orlowsky)

Vallejo, Apollinaire, Celan… You create your own context. What does it mean for a poet to be in the context of culture?

— Now, when an interest in Ukrainian culture has awakened in the world, we should try to introduce Ukrainian classics to the world in a new way. Create new translations, republish existing ones in new ways. For example, first introduce Pavlo Tychyna's "Clarinets of the Sun" collection as interpreted by the Ukrainian composer Valentyn Sylvestrov, whose name is well known among music fans around the world. Or illustrate Taras Shevchenko's poetry with his paintings and graphic works and show the poet as a very interesting artist.

I don’t believe this is the time to reissue the full academic edition of Shevcheko’s Kobzar in translation, it would be much more effective to publish small collections of selected poems, perhaps even different poems for different countries. For example, Poles and Jews should not be reminded of the poem "Haydamaky," but rather be introduced to his less studied poems, such as Shevchenko’s retelling of ancient prophets or the very enlightened poem "Maria". These works would be a revelation for poetry fans in the English-speaking world, where readers could see parallels with the poetic language of William Blake.

Or why not rethink the same "Maria" and other poems such as "Bondwoman", "Witch"? Maybe even in the context of Lesya Ukrainka’s dramatic poems with her amazing female characters—from the fabulous, mythical Mavka to the classic Cassandra? Wouldn't it be wonderfully fascinating if against the background of both the individual and collective image of Ukrainian women, unexpectedly, in these nearly two years of great modern drama, we opened a new way of seeing them?

I suddenly remembered one of my old poems during this time of war—"Kateryna". I wrote this poem more than thirty years ago, it is not so much about Shevchenko’s poem "Kateryna," as about the Kateryna of Shevchenko's painting. A copy of Shevchenko's ‘Kateryna’ painting hangs in the living room of our home, in a wooden frame my grandfather made. My father painted it in 1942, being twenty years old, in his native village in Sumy Oblast, during the German occupation. Only when I was writing my poem, did I suddenly notice that the posture and facial expression of the Kateryna in the painting was not at all as I imagined her from Shevchenko’s poem. In the painting, Kateryna’s downcast look as she passes a fellow villager, who is carving wooden spoons (like my carpenter grandfather), is not about the shame of dishonor and not about the hopeless weakness that will lead to her fatal downfall. It is a deep focus on herself and her unborn child. It suddenly occurred to me that at that moment on Shevchenko's canvas, the pregnant Kateryna made a different decision from the one she made in the poem.

It was March 9, Taras Shevchenko's birthday, or maybe March 8. I don't remember if I slept at all that night and when I first saw that photograph of a young woman in front of the Kyiv train station. Carrying a rifle, she was leading a little girl by the hand. It was not clear whether she was the mother, an older sister, or a special escort for the child. Perhaps she herself was handing the child over to someone on the evacuation train, for example to her husband, and then she would continue to the front. "With children and rifles in dead hands!" And I remembered Kateryna, who leaves her son by the road where the kobzar minstrels will pass, and throws herself into a cold winter lake. And here is another Kateryna, with a child and a rifle, going to war for her country.

If we interpret our classical literature through the experiences of modern war, then we will lose something. And I'm not sure what exactly. In the early days of the Russian invasion, a friend sent me a photo of the luxurious lace lingerie she was going to put on to wear in the bomb shelter, accompanying the photo with a quote from your poem. You know which quote I mean. And what will this poem be about now?

— The poem "Rose" ("It's time to pack the bag and leave") is completely symbolic, it is about the Last Journey.

Two or three brushes, soap and a towel.

Clean underwear, just in case your lover

meets you – or God. Either way,

you should have clean underwear.(Translated by Dzvinia Orlowsky)

I could have left Kyiv on February 24, together with my daughter and her child, but I stayed. There was nothing heroic in this. The tens of thousands of women with suitcases leaving with their children, going into the unknown, that was heroic. I will always remember my granddaughter’s knapsack which she packed herself, containing colored pencils, a couple of children’s books, her favorite doll and several soft stuffed animals.

Initially, I was in a stupor. And then I also packed such a "suitcase"— with documents, medicine, water, an apple and chocolate. A temporary shelter opened in the basement of our house, but really it was just an abandoned basement with eternally wet pipes. In the first days of the war neighbors hid there from shelling. I was getting ready to go to that basement in the evening with my packed bag. I thought about it and put a spare set of underwear in my suitcase. But I did not go into the basement, I sat by the wall of my apartment until morning. I never went to the bomb shelter.

Later I heard that many older people did the same, every evening they put on clean clothes and a change of underwear in the suitcase with the documents just in case.

After the Kyiv region was liberated, I read about a woman who described how her older relative refused to leave her home. She spent the entire time of the Russian occupation in her high-rise apartment, rarely leaving the house. She never once went down to the basement during shelling. Her explanation was that if she was destined to die, then all the people in that basement will be torn to pieces, and when the rubble would be cleared, they will not know who is who, and they will not be able to put her back together, because they will not know whose leg or arm is where. It is better that I stand before God in my house, she said, where there will be only me and my remains. I understood this immediately, and for some reason, I imagined this woman in her shelter—well, perhaps not in lacy lingerie, but wearing shoes and tights, a dress, a scarf on her head, ready to meet God.

What are these stories about?

— One day I found the word to describe this inner state of many Ukrainians during the war. Not heroism, (there was and is heroism, but it is rather manifested in exceptional actions and human characters), but stoicism. A stoic person can also sometimes become a hero, or can just be a human. Everyone chooses their own way of coping.

I remember when I left the house for the first time. Kyiv was quiet: no cars, no people. Cafes were closed, shop windows were shuttered. Only one boutique on the Passage had its window open. The mannequins were dressed in the "new spring-summer season" clothes, they were all as incorporate and sexless as angels, one even had a suitcase in his hand. I stopped and looked at them, and they looked at me. And suddenly I realized that the mannequins had no eyes, only empty eye sockets. And they did not look at you, but through you, with such a decisive and stubborn expression, ready to continue on their journey.

That was the picture of Kyiv's stoicism for me.

Were you not disturbed that the war had somehow remodeled your poems and now, connected to the war, they had acquired a new content?

— Quite the opposite. I think this is wonderful if one can say that something can be wonderful during wartime. A poem of mine that is often mentioned in this context is "Deed". I wrote it during my short fascination with Zen Buddhism. There is a seppuku scene at the end, for some reason, everyone sees God as the assistant holding the sword over the head of the samurai... Perhaps there is some visible similarity.... But mostly they quote "Stand straight, look at yourself." I even chose these words as the motto for two of my talks in Kyiv and New York. And now they are just about stoicism.

Stand straight, look at yourself.

Fear nothing and no one:

not the touch of the bare sky,

or the sting of stone.(Translated (by Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky)

Any work of art, including poetry, is not only about what the author wanted to say or has said, but also about its reception. It’s like folk songs, when the author is very rarely known, but everyone who sings or listens to a folk song feels like its author—a part of the anonymous people.

Here’s a funny incident that happened. I was looking for the "We will not die in Paris" video by the group "Dead Rooster" for a presentation, and I came across Mis’ko Barbara and Sasha Koltsova and other musicians in some cafe, with young people dancing. In the comments to the video, someone writes: "Who is Natalka Bilotserkivets?" Someone immediately responds: "It’s that singer." It was like a dialogue between two anonymous people, and suddenly everyone became anonymous. I like that.

I notice that most of your poems are written in the second person. Is this how you delegate your experience to the reader – do you just give it all without any residuals? I wanted to ask what you get in return, but now, it seems, I already have the answer to this question.

— For me the second person "you" is not about giving away your "I" but about belonging and kinship (I'm like you, you're like me). Poetry in the second person was generally quite common in my generation, and interestingly, primarily among male poets, but not among women poets. Earlier I often used to write in the first person, and still do from time to time. Somewhere from the end of the 1990s, since my "Allergy" collection was published, I write "you" deliberately. "I" is very individual, and I always wanted readers to read my poems as if they were about themselves, regardless of age, gender, nationality, etc.

For example, the poem "Hotel Central” was the best received at my readings abroad, maybe because the audience consisted mainly of Ukrainian refugees. They saw their temporary refuge in the symbolic "central hotel" and themselves in that poetic "you". And in return, I get the feeling of a single human family.

When I presented my book in New York at the end of March this year, Ali Kinsella wanted us to read one of her favorite poems, "February". Perhaps because February in Ukrainian is Liutyi, which means ferocious and that word could be literally translated as "the cruel month of February", and therefore speaks to the events of both February 20, 2014, and February 24, 2022.

But the poem was written in 2002, and it contains the following lines:

My princess, wife of fish and frogs!

Your every son – a scoundrel or a slave!

Whom to give oneself to and whom to love?

On the banks of the eternal river –

accountants, majors, their wives,

their children sent off to foreign schools.(Translated by Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky)

Although I love this poem, I told Ali that I would not read it now. Because the image of Ukraine, of the Ukrainian people in that poem, is not the same as what we all felt it, maybe for a short period, after February of last year, when all Ukrainians, unexpectedly for themselves and for the world, rallied around the flag.

We should not air our dirty laundry in public in order not to spoil the image that is currently being formed about Ukraine in the world?

— No. Nearly everyone present at my book presentation at the Shevchenko Scientific Society in New York City was Ukrainian — if not by citizenship, then by origin. It seemed to me that this was not the time for such bitter words, even if they were true. There are moments when poets must speak, like Panteleimon Kulish did in the poem "To my native people" —"A people without a path, without honor and respect" and other times, when they speak like Pavlo Tychyna "I am a people whose strength of truth has not yet been conquered by anyone". I did not want to violate this feeling of unity.

I recently read something interesting, that the best works about war will be written by those who did not actually fight directly. I even allow that the best works about our war, primarily cinema and prose, may be created by non-Ukrainians and not in Ukraine. For those who have been on the battlefield—and we have writers who are fighting—they will obviously find this a bit disturbing. Depends on the person, of course. They will be disturbed by this division of "unequivocally good—unequivocally bad", a hero has no right to be weak, a hero must be a hero in battle, and not hesitate.

I once read "The Young Lions" by Irwin Shaw and watched the film based on this novel by Edward Dmytryk (an American director of Ukrainian origin). The novel was published in 1948, the film came out in 1958, and in my opinion, the film is more interesting and powerful than the book. Among the heroes of the film are two young Americans, and Marlon Brando plays a German officer. At the beginning of the film, they are all civilians, the future German officer is a ski instructor at a winter resort in Bavaria, a Nietzschean man with aesthetic sensibilities, who believes that Germany needs to be "made great again". The stories of these "three World War II soldiers", as one American critic wrote, are first presented separately. They meet in the final part of both the film and the war, in a scene where one of the Americans, seeing a figure in the distance, shoots and kills the German officer.

What was most surprising to me was that Brando didn't turn his character into a complete scoundrel or a good-for-nothing. His character, as another contemporary critic wrote, is rather an ordinary decent person who was deceived and used. Brando portrays him with compassion—and this is precisely what infuriated Irwin Shaw the most because in his novel there is no kindness or sympathy for the symbolic enemy.

And so, I thought that a contemporary Ukrainian writer, especially one with military experience (like Irwin Shaw by the way), and a contemporary Ukrainian film director and actor, would also not be able to accept such a "sympathetic" view of even a "conditionally good" Russian, much less an enemy on the battlefield. Certainly not now, not even three years after winning the war, as was the case with Shaw's novel, and perhaps not even 13 years later, as happened with the film. At present, in Ukrainian literature, this "other" can only be depicted as a complete miscreant or an absolute bastard. And this is understandable and justified at present. As for later, we’ll talk about that later.

Why must there be Russians in our war novel?

— Because this is Russia's war against Ukraine. Because in a novel about war, there must be battles, it is impossible to do without them. And we cannot but call Russia Russia, we cannot call Russian soldiers not Russian.

For those who were on the battlefield—and we have writers who are fighting at the front—it can be ubearably difficult for them to move away from the inescapable battlefield perception of only "black and white", absolute evil and infallible good. Maybe individual short black-and-white works of a "high" nature are possible, but not grand-scale—not only in the sense of size, but also in terms of complexity of plots and characters. And it is even more difficult to imagine that someone could now write a masterful novel-screenplay not so much about the war, as about people during the war, where war, as a separate character (or a director or screenplay writer), a kind of Lucifer or Mephistopheles, interacts with people and wields them. And where the hero is a person who is capable (or incapable) of enduring and surviving.

Might I assume: you don't read our military and veteran literature that much?

— Not much, to be honest. I read Chapeye, Chekh, Aseyev about the Donetsk "Isolation" prison, Rafeyenko about refugees***. Poems about war.

Poems are the most difficult. Poetry is probably the most formal of art forms; it can be compared with music in this regard. Poetry requires careful and diligent work with the form. Is it possible to think about mastery and form, rhymes and rhythm, epithets and metaphors, stanzas and punctuation, when you and everyone around you is thinking about how to hang on, survive, fight and win? As in Theodore Adorno’s well-known dictum from 1949 —"To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric". It is unlikely that he meant that no poetry is ever possible after Auschwitz, but that truly lofty and beautiful poetry is impossible. Because at a time of great tragedies, it is immoral to think about beauty and perfection.

At the beginning of this war, many Ukrainian poets admitted that they were unable to compose poems. And yet poems were written after Bucha, Mariupol, Izyum, Kherson. They were composed by non-professional and established professional poets. Some of the poems became songs (like Sviatoslav Vakarchuk's song about "the City of Mary", or Serhiy Zhadan's song about children in the Kharkiv metro), others were included in “war poetry” anthologies... and mostly stayed on private pages on social media. Can we consider such impulsive, tremulous poems to be High Art, or at least fiction that will survive its time, as happened with the great novels about the First and Second World Wars?...

A year ago, I was in Paris for a meeting with an American documentary filmmaker. When asked if he would like to shoot "an artistic film as well," he answered that the question was inappropriate because a documentary film is also a work of art, it must be and is artistic. Perhaps in Ukraine we are now witnessing the emergence of literature and art that is new for us, and has different requirements and approaches, and where the philosophical question of the beauty of art arises in a different dimension. A type of parallel with fiction literature. For a time, it will dominate and coexist with so-called high poetry and great novels. And then for the most part it will go the way of the literary archives or become a source of inspiration for future artists.

And someone will write a beautiful poem about poems during the war.

***

• Artem Chapay, Ukrainian writer, novelist, reporter and translator. He writes fiction and creative nonfiction and is currently serving with the Ukrainian Armed Forces at the front.

• Artem Chekh, is an award winning Ukrainian writer and journalist. He took part in the war in Donbas in 2014 and has been fighting with the Ukrainian Armed Forces on the front since the February 2022 Russian full scale invasion.

• Stanislav Aseyev, Ukrainian writer and journalist from Donetsk, held by Russian proxies in the Izoliatsia prison for 963 days. Released as part of a prison exchange in December 2019.

• Volodymyr Rafeyenko, born in Donetsk, Rafeyenko is a Ukrainian writer, novelist and poet. Fleeing Russian occupation in 2014 he settled outside Kyiv and committed to writing only in Ukrainian.

Natalka Bilotserkivets is a Ukrainian poet and essayist. She has published six volumes of poetry and several editions of selected poems. The collections Allergy and Central Hotel were Books of the Year in 2000 and 2004, respectively. Her poetry has been translated into several languages (primarily English, Polish, German, and French), and distinguished with many national and international awards. The English translations include Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow, translated by Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky, published by Lost Horse Press (2021), and Subterranean Fire: The Selected Poetry Of Natalka Bilotserkivets, translated by multiple translators, published by Glagoslav Publications (2020-2022).

In recent years, Natalka Bilotserkivets has been writing prose, but after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, she returned to poetry.