Virlana Tkacz – director, researcher, translator, director of the Yara Arts Group at the LaMama Theatre, New York.

The interview was made during her residence at “The Word” house which is administered by the Kharkiv Museum of Literature.

This interview for Craft was conducted in Kharkiv in a residential building with a name: “The Word” [Slovo Building, 'slovo' means "word" in Ukrainian]. This apartment house was inhabited by Ukrainian writers, the majority of whom did not die of natural causes. We are with Virlana Tkacz in the home of the writer and journalist Petro Lisovyi, who was also repressed by the Soviet authorities, but whose family continued to live here.

How do you feel about living here?

– It’s luxury! I can’t imagine how just one person could live here. Our whole theatre troupe fits in. We enjoy each other’s company. We make theatre together.

In my childhood, there was only one plaque on the wall of this house – it said that Pavlo Tychyna lived here. My father brought me here and told me that Pavel Tychyna was not the only one who had lived here. Tell us about your first visit to The Word House. When was it? What happened?

– It was December 1990.

I came here with Cherkashin (Roman Cherkashin – Ukrainian actor, director, and teacher - ed.) We talked a lot about Kurbas. Roman brought me here and said “You see! That’s where Tychyna is writing his poems and that’s where Kurbas is planning his stage shows and that’s where Khvylovy is shooting.” I thought to myself “That’s the Ukraine I understand: what, where, how? I brought flowers for Tychyna’s memorial plaque. People said “How can you do that?! He was a communist!” But I loved Tychyna’s poetry. My Grandfather read them to me, as a child, instead of fairly stories. They were my favorite poems and I still go back to them sometimes. There’s a sort of… a drive about them. Even in the political poems, there is something interesting.

You know we love to complain about how nothing changes fast enough in Ukraine, that reforms happen too slowly. But let’s think back to 1990. Could you have imagined then that there would be a residency like this, that you would be living in this apartment?

– That I would live here and write about Kurbas, and create an exhibition at the Arsenal? No! I could never have imagined that.

But here we are!

– Yes. Who would have thought that the Soviet Union would collapse? They say it’s all so futuristic.

This is “Berezil’s” jubilee year. Let’s speak about that – about “Berezil”. Cherkashin was a “Berezil” member – one of the few who remained. Tell us my favorite story about how you discovered Kurbas – how he became part of your life – then we’ll talk about “Berezil”.

– I heard about Kurbas from my granddad, but it didn’t register then. I regret it now, but it didn’t interest me. Tychyna was more interesting. Khyvilovy even more so. The short novel “I’m a Romantic”, for example. I read it at 16 or 17 and I was hooked! But Kurbas… I was doing my master’s in stage direction at university, and I had to stage something. I put on All God’s Chillun Got Wings by Eugene O`Neill. It’s a play with loads of contradictions – whites, blacks, the situation in the 1920s. My tutor said, “Look, Verlyana, you also have to write a paper about a director.” “Well, I’ll do O’Neill,” I said. “And it will take you 25 years! No. You need to find something more realistic. There must be some Ukrainian director you could write about.” And I remembered that guy my granddad had told me about – Kurbas. I went to the library, and there I found exactly two books about him!

And it’s true, at that point there were only two books about him: Hirniak [Joseph Hirniak, (1895 -1989) – the Ukrainian actor and director who was in the “Berezil” troop and who, in emigration, headed the Ukrainian Theatre in America.] He had written a long article about Kurbas and theatre which was published in English in the 1950s. And before that, there was only what Vasilko had put together [Vasiliy Vasilko, (1893 – 1970) – a Ukrainian actor, director, and theatre critic: one of Kurbas’ students.] As for the rest – the most interesting thing I found in the library at Columbia was an album – the first almanac of Ukrainian theatre. I actually had to cut the pages.

You mean, nobody had read that book before?

– Exactly. Nobody had read it, although it had arrived in the library in 1930 or 1931. Most of the books I found were either unread or had been read last by Luckyj, [George Luckyj (1919 – 2001) a literary critic, slavist, translator, and publisher] (You could tell because, back then, you had to sign and date the lender sheet on the inside cover – true, I didn’t always sign – it wasn’t required then.) Anyway, Luckyj had read it the year I was born! And he was the only one who’d read any of it.

I remember that Luckyj and Shevelev then wrote an article about the play “Maclena Grasa”.

– Luckyj actually wrote loads on things Ukrainian. I think, he and his wife translated “The People’s Malachai” [a play by Mykola Kulish (1927), which was staged by Les Kurbas with “Berezil”] or maybe something else. That was staged by Tairov [Alexander Tairov (1885-1950) – a theatre director and founder of the Moscow Chamber Theatre].

“Maclena Grasa”?

– No, possibly Maclena Grasa, too, but I think Kurbas didn’t stage it.

But Luckyj and Shevelyov wrote that article while they were still here in Kharkiv. But they didn’t publish it. It was lost.

– I didn’t know that, but I did find one thing that he wrote here. We didn’t have it in the West. I took it there.

What happened next. You wrote an excellent thesis, and you could have got a job on Broadway…

– From University to Broadway – that’s not a logical path. Academics don’t get to work on Broadway… they don’t understand that to work in theater you need special education – If you want to work on Broadway, you just go along to casting. Someone will want what you have to offer. Nobody even looks at your formal qualifications. Nobody writes about them. The actors I work with are creative people who like to write and discuss things, people you can enjoy rehearsing with – they read a lot. We create our own vision. But few people ask about your education or talk about it.

I would love to talk to Kurbas.

– Yes. There are lots of people I would love to talk to – I’d invite half the residents of this house [“The Word” apartment block] to take part in the discussion. Especially since Tychyna and Smolych talk about the relationships [among the residents of “The Word” apartment block] and attitudes towards them.

Tell us about the name “Berezil”.

– Oh, I know a good story about that, but it’s about me, not “Berezil”. I once came to attend a conference in Kyiv. It was 10 – 15 years ago. I got there late because I was just off the plane, and I went straight there and sat down at the back and listened to what was being said. It was at the Karpenko-Kary University and the title of the conference was “Kurbas and the World”. And they were saying how Kurbas had had a huge influence on the world. Well, okay, only the world hadn’t actually heard of him, but anyway.

It’s the message I try to put over too. I hear “There is a Theatre outside Ukraine that is greatly influenced by Kurbas, for example, The Yara Arts Group. They even named themselves the same way as Kurbas.” And I think “What?! Well, OK.”

And then he says: “Just as the name ‘Berezil’ comes from the word for March, so the word ‘Yara’ comes from the word for spring. They don’t call themselves the Yara Theatre, but ‘The Yara Arts Group’. That’s exactly how Kurbas named his troop ‘The Berezel Arts Group’”. And I was thinking, how nice! From now on, I will say that. Who thought about such things? Certainly not me.

Tell us how the names “Berezil” and “Yara” came about?

– Well, “Berezil” – that’s a serious business. It always seems to me that they had a serious story, whereas, I have a comedy. There is a question mark over exactly when the name “Berezil” appeared. But Kurbas translated Bjornson’s poem “I Choose Berezil”. [by the Norwegian poet B. Bjornson “I Choose Berezil” – He breaks all the old ways, breaking through to a new place…”] But that poem is not about March, but about April. He makes use of it but breaks the stereotypes. It’s a super name for a theatre, isn’t it? It strains towards the future. I think it’s very entertaining – exactly right for the 1920s, for Kurbas, Meller [Vadym Meller (1884-1962) – artist, cubist-futurist, constructivist, who worked with Kurbas]. They were imagining a future that is much bigger than all of us.

But there was a competition with a bottle of wine as the prize.

– That’s another story – a well-known one, told by Deich [Alexander Deich (1893-1972) – theatre critic]. They were looking for a name and everyone had their suggestions. Tychyna had a good idea – ‘The Garden’ (‘Sad’, in Ukrainian). And everyone laughed because someone said: “That would make us all sadists!” I like it. There were some more wise suggestions and then Kurbas said: “Berezil”. The idea was accepted unanimously.

Now tell us about “Yara”.

– How we chose the name? It was completely random – like ‘Sadism’. We wouldn’t be called ‘Yara Arts Group’ had it not been for the friend who registered us. “La Mama” was having some financial problems – the usual thing in the theatre, you know… Mr. George wrote to me and said “Virlana, you need to take your money out.” I didn’t have a lot of money tied up in the studio – about $1000 – that’s all. And he asks “Who should I transfer it to?” And I said, “Maybe to me…” But then I would have to pay 30% tax – that’s a lot. And Mr. George asks, “Don’t you have a group?” – I didn’t – and he says, “Go and register one!”

So, I phoned my friend, a lawyer and we had dinner and he said: “Ring me up and leave a message on my answerphone with the name of the group – choose a name for yourselves.”

I had taken a cake to dinner – it was the 25th of February [Les Kurbas’ birthday]. We had done a play about Kurbas. Kurbas did not actually appear in the play – only slides from his diary. It was about young people who were always talking about Kurbas, but he wasn’t actually in the play. The action took place partly in the 1990s and partly in the 1920s. We were all trying to decide what to focus on – on what the characters wanted to do or on what actually happened to them? – They were all executed. I said, “How about we form a troop?” and someone said, “At last, the right idea!” “Only we need to come up with a name,” I said. Watoku Ueno immediately said, “I have an idea!” “OK, go ahead.” He says: “Since we are all eastern, we should be called ‘Rice and Rye’!” Everyone fell about laughing – are we a cooperative or something?!

And Wanda Fips says “That’s a great idea!” She was always prepared to be the diplomat when Watoku said something bizarre. “Yes, Virlana, we translated a poem once … something about rye… or wheat.” And I say: "Wheat? What kind of wheat was it?… Spring wheat!” As soon as I said ‘spring’ (in Ukrainian “Yara”), that was that. “That’s great! Everyone knows how to write it – not like my name!” In Indian it means friend, it’s ‘light’ in Arabic. In Brazil it’s a water goddess or something. In native American it means ‘arrow – flying to the target’.

So, I phoned my lawyer friend and said: “We’re called Yara.” And he went along to register us, and he was thinking, “What do they actually do?” He’d forgotten that we were a theatre group, so he thought he had better go for something all-encompassing – “Yara Arts Group”.

That’s how it happened. So, Kurbas did inspire us.

You see, it’s all about a cosmic connection.

– Yes, it is.

But they were right, at the conference in Kyiv.

– Yes. They were right.

You do sometimes learn something about what you are doing at conferences. “Berezil” was born in Kyiv.

– Yes. In 1922. Interestingly, our first play ended with that.

They performed in Kyiv, triumphant, but simultaneously they suffered their worst defeat. They left for the provinces, not to tour, but because it was impossible to survive in Kyiv. It was 2021 and they left for the villages. Partly because people could feed them there. Then they came to Kharkiv. Hryhoriy Hrynko [(1890 -1938) economist, politician. In 1920 he headed the People’s Committee for Education of the Ukrainian Socialist Republic] sent them a telegram saying that the National Theatre would be here – in 1921, in Kharkiv! So, they came here. It took them ages to get here. Nothing worked at that time. And the nucleus of the Molodova Theatre [The Youth Theatre directed by Les Kurbas which worked in Kyiv from 1917 to 1919] completely fell apart. It was already pulled apart.

Gakkerbush [Lyubov Gakkerbush (1888 -1947) – actress] and Vasilko and all their colleagues could see that the situation was hopeless. How could you have an experimental theatre in 1921! But later they all returned to “Berezil”. But the situation was completely different. It was no longer a community based on the belief of equal people in a common ideal – now it was really Kurbas’ theatre. And they were really working with the very youngest. It works best with young people who don’t know anything. Then we all learn together. When everyone knows everything, it’s very difficult.

Let’s try to say something about Kurbas, for those who know nothing about him. In the 90s did people here know anything?

– “What is there to say about Kurbas? We all know!”

At that time, when people didn’t even know when he died?

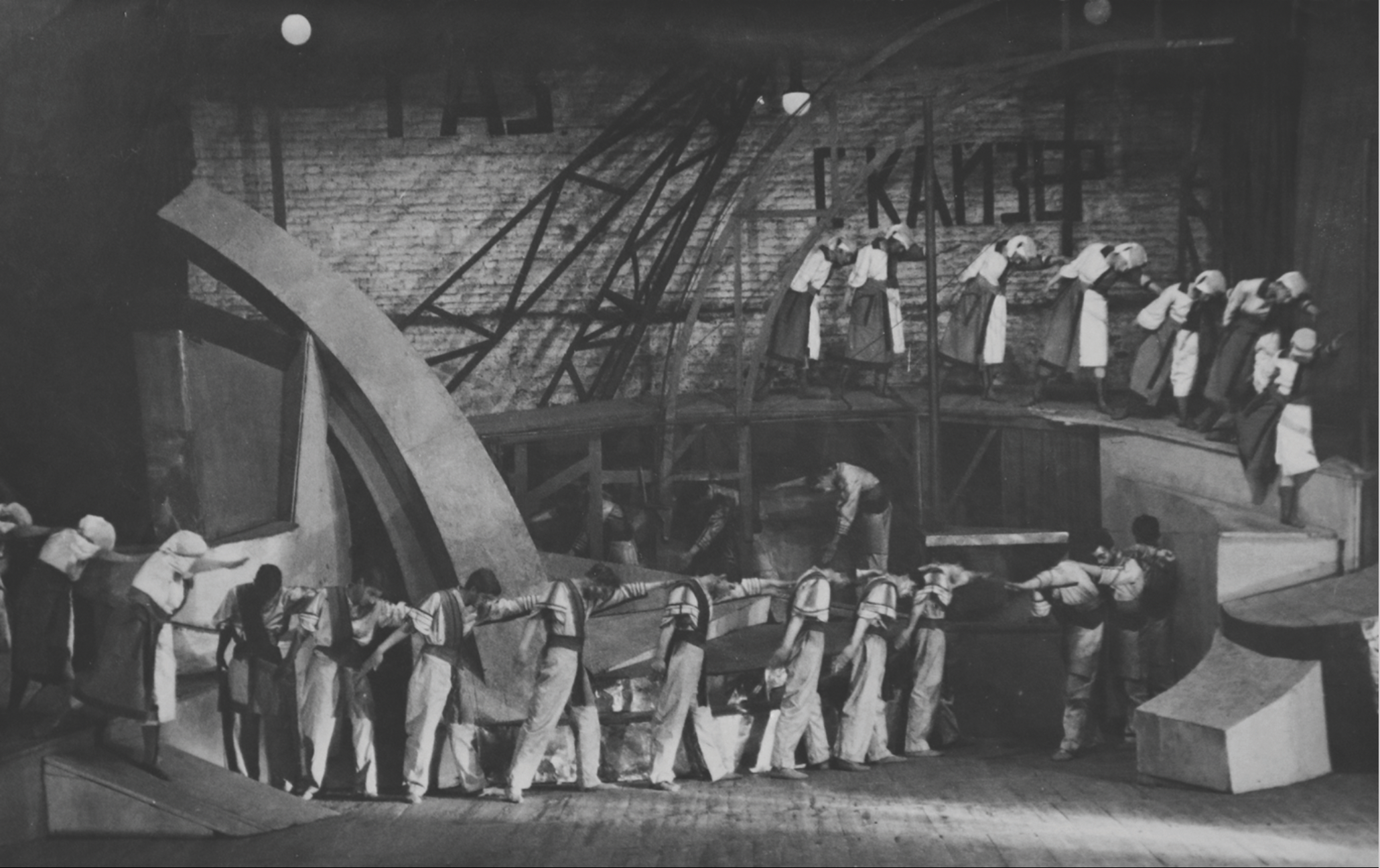

– Where he died? I never paid attention to his biography and still don’t. Not just because it’s so sad. Biographies have never interested me. I’m not even interested in my own biography. [see Svetlana Oleshko’s biographical interview with Virlana Tkacz on the Misko Barbara Blog channel] I was interested in what he had done. We all know that Malevich painted his Black Square, that Picasso drew two noses. We all have our own ideas about that. But what did Kurbas do? Ask anyone. Nobody knows a thing. And that’s the most interesting thing. What did he do? Why is he so interesting? Knyazhytsky [Mykola Knyazhytsky – journalist, Ukrainian member of parliament] once asked me on TV. Did he really show the movement of an exploding factory? In “Gas” [directed by L. Kurbas in 1923 based on the play by the German playwright George Kaizer] It’s unbelievable! Only actors on stage – nothing else! How did he do that? It was action, inspired by Nizhynska’s dancing [Bronislava Nizhynska (1891-1927) – dancer and teacher]. And Butzkov’s music [Anatolii Butzkov (1892-1943) – composer, music historian, and critic] It was a different conception of theatre, of what theatre could do. Of what a person could do on stage.

A person on stage can be what he believes in, what he is. He can turn from a man, from a machine worker, into the machine that he works on, or into that exploding gas and not only into the gas, but into the bricks. And at the end, there are the victims lying there. It’s fascinating. And that was in 1922 – 1923! Super!

That’s one things, then there what they did in “Jimmy Higgins” [An Antony Sinclair play staged by Les. Kurbas in 1923]. They used film to show what a person is going through deep down. It’s super! Now we all use multi-media – bang, bang, bang, but we can’t show that. That’s just flashing lights. It’s not the same.

Obviously, it’s not a well-known fact that Kurbas was one of the first to use multi-media in the drama theatre. Tell us about “Jimmy Higgins” and about these emotions.

– Well, you know there was film in the theatres. Where else could it have been? But mostly the stories were adventures or geographical – they showed monkeys in Mozambique, and then the Amazon, how water flows. It wasn’t all around one theme. But it teaches us the language of film, and now we understand it perfectly, but you have to imagine how people understood it in 1922. It was very gradual. For example, in the first scene, the meeting scene in “Jimmy Higgins” – here we definitely have multi-media. It’s not me who come up with the idea – as an academic, it’s written in the script. The play is based on an American novel, and he uses multi-media there (It’s written there). There are extremely exact directions: how music is used, the electricity, film. What they do with this is very clear.

First, someone says “The Germans have entered Belgium.” And then they show that. You can go to the Pshenichnii Archive [The G. S Pshenichnii Central film archive] It’s there. The Germans went into Belgium. It’s newsreel. And they didn’t have 20 cameras there when the soldiers went past – they had only one. You see one explosion and then another and you begin to see how he uses it. You go to the archives and look at those films, but most people don’t go. They write theories about what he was thinking. But what did he do and how did it look? How did it work? You see that film and it shows what the actor is saying. And in the next scene, the actor isn’t speaking. You’ve only got the film.

Or the actor says a sentence and then the film takes over. In the third scene, we see how the actor reacts, how someone else reacts… That is how slow multi-media is used. There are 36 fragments. The director is teaching you how to go forward, what could be the next step. It’s very curious. And the most interesting thing – how they show the explosion – we are, as it were, inside the action.

As if the catastrophe, the explosion, is happening to us. Time starts to work differently. And we see with our own eyes that something is coming at us. They start doing amazing things: the road runs away, and the camera returns, and you suddenly see it! Every single step has been mapped out. That is how Kurbas did it.

Many of the films are no longer in existence. They weren’t purposely destroyed. They were on celluloid film, and it doesn’t last forever. But the most interesting thing is that in the last section of the performance he uses the language that he has been teaching you. And he also works with people. He shows the movement of gas from the factory – it’s depicted through the movement of people. Here he doesn’t use film, only the human body. The factory has several floors and this reality is reproduced allegorically. And when the main hero begins to lose his reason, it is shown by actors front stage. All the actors act out different moments from the play and run about the stage as if they are the thoughts rushing around his head because they are torturing him up there.

But there was no physical torture? Nobody tortured the actor. How was it done?

– There was no need. They only made noises and he took a cord and descended on the cord through his thoughts, as if he was being dissolved in his consciousness. And the thoughts around him berating him – a madness… and there was mother – liberty. And he comes up and returns back.

So, “Berezil” is created in Kyiv and earns itself great status and the reputation of the best avant-guard theatre in Soviet Ukraine.

– Perhaps the most important thing was the theatre space. Because this was very hard to find.

It’s at that moment that “Berezil” is more or less forced to move to Kharkiv, to the new capital, which, at that moment was nothing like a capital. It was a provincial town, with no suitable spaces, no auditoriums. What happens?

– There are no auditoriums, but they stage a show. The first one was problematic. They did it with one actor – a great actor – Buchma [Ambrosii Buchma (1891-1957) – actor, director] But he suddenly gets a role in a film. It happens to us in New York too, so we understand how it works. You create a play around a specific actor and that actor leaves. It’s very difficult to find a way around it when a play is custom-made around a specific actor.

In short, nobody liked it and they were thinking about what to do next. A musical. They brought in other directors.

In Soviet times, it was not the critics who decided who did what. Various administrative bodies decided. And sometimes this was good and sometimes bad. They also decided whether to give you an auditorium and an audience.

It was a very difficult and completely new environment. You knew exactly how many tickets would be sold, who the audience would be. People would come and throw tomatoes if they didn’t like it. There is a kind of dialogue between the audience and the actors. But the audiences were not random folk, forced to attend the show. It took some time for these administrators to understand how things work. They were practically theatre producers…

Perhaps we need to explain the context. It isn’t as if nobody in Kharkiv had ever heard of anybody. Afterall, Meyerhold made guest appearances here.

– Yes. And Kurbas came to make guest appearances too – but that means two or three shows, not six weeks. It was difficult. They didn’t do long-runs in Kyiv either. It was like on the US stage – they performed as long as they could, but not every day. They did repertory. It was a production company as they called it here.

Kharkiv loved The Sinelnikov Theatre. That was its canon. As Shevelyov wrote, it was the best provincial theatre in the Russian empire. But Kurbas and things provincial – that was…

– But I spoke to Tanya [Tetyana Turka, actor] from the Shevchenko Theatre. Sinelnikov was only in that theatre for a short time. Before there were different companies there. And Ukrainians built that theatre.

For example, Aldridge [Ira Frederick Aldridge] performed there. Different actors from all over the world.

Kitka-Oscnovyanenko joined the theatre, and people are surprised that Kropyvnytskyi is buried in Kharkiv. And the Korifey Theater was here. But Korifey and Kurbas – again they are …

– Mutually exclusive ideas.

The avant-guard theatre had a problematic relationship with the party and even more so with audiences. Who went to avant-guard theatre? Mostly it was students, who could understand the themes and ideas about culture. That nucleus around which everything is built and to which everything is attached. There was none of that there at first.

Two or three years later everything started to work. But it was a big theatre. You walk out onto the state of the Shevchenko theatre and it’s massive – like for an opera. It’s very difficult to fill that space. So, you have a problem with the audience.

I suggest we jump a bit now. Kurbas did find a strategy. At first, Kharkiv ignored him. The auditoriums were empty, or the reaction was cold. But he tried to compromise. He invites foreign directors, puts on musicals. Though they weren’t just silly entertainment.

– No, no! Those directors that he brought in like Inkizhinkov [Valerii Inkizhinkov (1895-1973) – actor, director] were very interesting.

You want Meyerhold? Here’s Inkizhinkov. Who actually created biomechanics? It wasn’t Meyerhold. Inkizhinkov was more Meyerhold, than Meyerhold himself. So, it was really interesting. Kurbas’ strategy was very wise.

I have tried to understand how it all worked. But the situation was very complicated. Kurbas at last started to understand Kharkiv better. And he found people to work with here. After all, he had arrived with a very western Ukrainian troop. He found Kulish and that’s when the magic started. We see him in “Hello” [“Hello, Hello on 477 Medium Wave” the first jazz review in Ukraine, presented on 9th January 1929 by the “Berezil” theatre in Kharkiv] or in the shows based on plays by Kulish.]

We see how multi-cultural Kharkiv is. Kurbas brought a very strong team to Kyiv, from the west. Also, from the west, he brought a designer, Meller [Vadim Georgievych (1884-1962)] A unique costume designer. But who does Kurbas find in Kharkiv? Kulish is from Kherson. And here there is the question of the local language and local way of living. I think there was a strong synergy between them, between the director and the writer, the director and the designer. Kurbas and like-minded directors around a design team: writers, composers, actors – then it’s another matter.

But Kurbas found himself in a situation where he had to build everything – he had to educate the audience, educate the playwright (Kylish), whose earlier works were nowhere near the level of Kurbas. He practically dragged Kylish up to his level. He had to educate the actors. We all remember that Yzhvii was not a cultured actress. Who was cultured back then? Buchma was making films. Within that 7 years everything had to be …

– Created. Yes. Created.

But I really like your theory that it wasn’t a difficult task for him, it wasn’t something new. He already knew how to create a good theatre. And here he goes out beyond the confines of theatre.

– Because, in Kyiv the aim of theatre was completely different. That was a dialogue with the avant-guard of Europe. Because culture is a continuous dialogue – with the past and with people of different countries. It can’t be created out of nothing. You see something different, and you react to that, or you read something, and it inspires you. That is how culture is born. And I think that the culture of Kurbas in Kyiv was directed at the all-Ukrainian audience. For him Ukraine was Europe. And why not? I thought so too: you’ve got Africa, you’ve got Europe. What else is there?

But in Kharkiv, apart from the theatre, you have to convince them that they are Europe. Kharkiv didn’t identify itself like that. And apart from that, there was the task of building a capital city.

– Building a capital, building a society differently. What is a society? It’s an all-consuming undertaking – everything taken together. The creation of a new culture. New space, new ways, the acceleration of the future.

Was the project successful? What do you think? Seven years, or a bit more (it wasn’t only Kurbas doing this) – well, they had about 10 years. Was the project successful? Did they break through into the future?

– That dialogue has continued up to today. So yes. Perhaps they found their audience only 100 years later. We are their future. Without them, we would not be here.

Without them there wouldn’t be anything, but back then the students you describe – Shevelyov, Luckij – they were that audience. How do we know about all this? It’s thanks to their descriptions, the details they give. Shevelyov wrote that “Maclain Grasa” was a masterpiece which he compared to Stone Henge. Let’s speak about that. About the later productions. About “Myna Mazailo” and “Maclena Grasa”.

– I find “Mina Mazailo” very interesting although at first, I didn’t think much about it. It’s comic. Everyone is sitting in one room, walking about. Crazy. But the direction keeps your attention!

It’s amazing! I think it’s the most powerful work from the point of view of stage direction. Where you’ve got the entire cosmos on the stage – the past and the future. Why does he do that in this play where everyone keeps banging doors and they don’t talk to one another. How can you imagine it? How can you begin to think about these spaces and what they represent? And then understand. We found these glass slides of the ancestors and began to understand.

Everyone throws out that scene because it’s very long and you need four elderly actors [refers to glass negatives of photographs of the stage for “Berezil’s” “Mina Mazailo” from 1929]. What was it all for? The ancestors are the most interesting aspect of the production – the way they speak to us. If you change your name, who are you? It’s so clever.

It’s fantastic! It is what culture is about – talking with ancestors and with those to come who will be the future.

I think they would have liked this play to become outdated, but it won’t.

– For us, it’s a bit unexpected. Everyone reads, people younger than us, everyone knows this play. It’s in the school curriculum. This is a recent thing in Ukraine. People who have been at school recently are growing up into real academics. They know much more than we do. They’ve been reading it from their childhoods.

And Aunt Motya from Kursk – she lives on.

– It’s true and I’m telling that she will continue to live on. There will always be people who think about changing their names.

From Scribe to Diamond.

– But listen: they have put stars in Nikolsky. And who are the stars? I went to see for myself. There was talk about whether Cossak Kharko would have a star. Is he a legend or a historical figure? I went to look and I couldn’t believe my eyes.

Kurbas has a star! So now you know. He’s among the legendary stars of Europe.

I need to explain: Nikolski is a new shopping centre. It was built in the heart of the city, a the beginning of Pushkinska Street, where they shouldn’t have built anything. I haven’t been there. I don’t want to go.

– But go and see the stars. It’s on the first floor. I went to every floor even though there was no electricity to see it all.

So now we have to go and see the Kurbas’ star. Now let’s consider Kurbas’ image. There’s a sculpture of him in Shevchenko Garden. It’s awful. Ridiculous. I can’t understand why this sculptor took off Kurbas’ shoes and shows a polyglot, a European barefoot!

– Well, I suppose he brought him down to his own level.

Let’s talk about “Hello, hello 477”. Why are you staging this?

– Because we found the score here. At the Shevchenko Theater Museum, they said there was no Meitus score. And Meitus is a very interesting person. Just like Butsky was Kurbas’ composer in Kyiv, but he went to Leningrad and didn’t go to Kharkiv.

So here Kurbas finds a young student at the conservatory who has a jazz band and who writes for jazz bands. It’s very interesting how Kurbas found all these different people. He finds Meller, who’s of Swedish origin, born in Leningrad. Meitus, a jew from Kropyvnytskyi. But who does he study with? Neuhause, Schillinger! Gershwin studied with Schillinger, who taught here at the conservatoire.

But nobody thought anything of that here. So Chistyakova [Valentina Chisyakova [1900-1984 – actress, wife of Les Kurbas], she is Russian. She becomes a Ukrainian actress. My grandfather always said “We all chose to be Ukrainians and so did they. They all chose to live in The Word House and that was its strength – that people chose to live here.

So why did you choose “Hello, Hello 447”?

– Well, I think it’s an interesting story. A jazz musical from the 1920s. It seems like Mattus wrote some stuff too. I brought it to Anthony Colman [Amerian musician, composer], who is a very interesting musician. He worked a lot with this kind of material. He was the first one to look at it (Everyone had told me ‘this is not jazz’) and he says: “Oh, something from the 1920s, where did you find it? I’ve never seen it before.”

I understand you’ve been researching for a long time.

– We are trying to understand the story. There’s no text. There are only 20 words written in the score and several songs.

And who wrote these unique texts.

– The directors and Johansen.

Johansen and Cherry. That part is about themselves?

Johansen wrote various parts of everything and the directors created the scenes. I know this. I understand how it works, what the options are. It seems to me that we have a habit of talking sadly about those times, “And they were all shot!”

But there were other moments, before that, when nobody could imagine it. When a performance is in full flight. This is what interests me.

It had been a difficult time – a pandemic. There was the Spanish flu in 1919. It was very hard. From the 20s – all that dancing and singing – there was a belief in a bright future – just in time, maybe.

I really like your style. Very few Ukrainian directors take your approach, with solid research… and there aren’t many books, are there? There’s no body of criticism that you could fantasize about. You work so sensitively. You more or less make a storyboard, like for a film: there are programs, you can see who played what. There are posters and sketches.

– There is a libretto in the program – you understand the order: what, where, how. This is the most important thing and not only who played. A few separate scenes also remain. But some of them you have to study hard to understand. In the 1920’s things had different names. Multiplicator. I think, what’s that? And it’s a cartoon.

And now you are selecting your team like Kurbas did, am I right?

– That’s the first thing you do. You understand who you want to work with. Because in the theatre, you don’t do anything yourself. The director doesn’t do anything. My mother says “What do you do? You just sit in an armchair!” Everyone else is running, jumping and I just sit.

Will the premier be in Kharkiv?

– I don’t know. I’m still not sure there will be a show at all. We take it step by step. I can never tell from the beginning: is it the right team, or material or approach? You have to feel your way.

But now, with you in Kharkiv, there is a designer or stage designer as we say. A composer will be joining you.

– Antony Colman. Zhadan is here too. And I am here. We are looking for musicians first. We need to start with that. It would be good to find a few singers.

Singers, step up!

– Jazz!

Don’t you think it is amazingly symbolic that this is all happening here in The Word House?

– All neighbors, yes.

When we got started. they would probably say: “That’s not right!” True, Kurbas was on the fifth floor, above us [Les Kurbas lived in “The Word House” apartment block]. He would have said “What are doing? A piece of nonsense?” We’ve come all the way from New York to sit here in confusion!

Illustrative materials from the personal archive of Virlana Tkacz

Translated by Elizabeth Kourkov

Virlana Tkacz – director, researcher, translator, director of the Yara Arts Group at the LaMama Theatre, New York.

The interview was made during her residence at “The Word” house which is administered by the Kharkiv Museum of Literature.